Update: See a follow-up post to this post and the comments, here.

Randall Wray bills this image — in wonkish humor that I know many of my Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)-savvy readers will get — as “The Most Subversive Sign Seen at the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ Protest.” Love it!

Which prompts me to finally publish this post, one I’ve been sitting on for months for fear of revealing myself to be the internet econocrank that I am. But here goes.

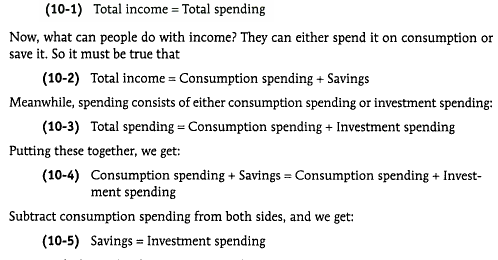

I’ve spent a lot of time over recent years deep in the national accounts (in the U.S., the National Income and Product Accounts — NIPAs), puzzling out how they work and what they tell us. In particular I’ve been puzzling about the S=I identity. I’ve read a lot of Kuznets (the guy who in the 1930s created the system, now used by [almost?] every country in the world), plus several of the leading economics textbooks, plus of course endless Wikipedia articles and academic papers, a tall pile of academic and popular books, and etc.

Why? Because the S=I identity has never made any sense to me, conceptually or theoretically, and it doesn’t seem to represent reality.

Clearly, private savings as we understand them — the amount individuals and businesses sock away, or the increase in individuals’ and businesses’ holdings of financial assets — don’t equal private fixed investment spending. Not even close. Ever.

The MMT crowd has helped greatly by pointing out what’s implied in the protestors’ sign:

Government surplus/deficit spending = Change in the stock of private financial assets (the right side of the equation being a pretty good definition of private “savings”).

That’s a real aha! insight into the national accounts, one with important conceptual, practical, normative, and political implications — far more useful (and accurate) implications than those associated with the S=I identity. More on those implications below.

But even the MMTers (that I’ve read) haven’t dealt with the accounting problem of real investment spending in the national accounts, and that pesky S=I identity. Since the identity is obviously not true, there must be something wrong with the national accounts.

I can’t believe that it’s taken me so long to figure it out. It’s obvious:

Savings is defined as equalling Income – Consumption Spending

But isn’t Savings, by any reasonable definition, Income – Spending? (Plus/minus price changes in financial asset values?)

And Spending = Consumption Spending + Investment Spending. (This is a sensible and accurate definition, though the line between consumption and investment spending is blurry.)

So:

Spending = Income

Spending = Consumption + Investment

Income = Consumption + Investment

Savings = Income – Spending

Savings = (Consumption + Investment) – (Consumption + Investment)

Savings = Zero

So if Savings = Investment, Investment = Zero

Something is really wrong here.

What’s wrong is the definition of Savings.

Understand: “Accounting identities” are not immutable laws engraved on stone tablets, handed down from some eternal and ethereal realm where All Truth Resides (as they’re often portrayed in the textbooks). They’re just definitions of terms, statements of accounting methodologies. Nothing more. (And — getting meta — this paragraph is a definition of terms regarding definitions of terms.)

Likewise: The national accounts are nothing more than a model or map of the economy, necessarily with defined terms and methodologies — with a great deal of effort expended to plug estimated numbers into the model.

And at the very heart of the system of national accounts, we have a patently false definition. How did this happen?

My explanation:

When Kuznets and company got together in the 30s to create the system, they were (necessarily) working from an understanding of the economy rooted in classical economics — an understanding that in this regard remains largely unchanged today. (In large part, in my opinion, because that understanding was codified into the system of national accounts itself; the understanding became unimpeachable. “These are accounting identities! They’re just true.”)

In that classical understanding, there is no (clear, regular, agreed, or even coherent) distinction between or understanding of the relationship between financial capital and real capital. (Marx is a complete conceptual mess, and the rest aren’t any better.) You constantly hear “capital” spoken of as a single undifferentiated lump.

Classical economics has never explained why the quantities of financial assets, and their prices, and their aggregate value, can plunge and skyrocket, while the real assets whose value they supposedly represent remain largely unchanged. (Aside from Keynes’ “animal spirits.” Thanks, John, for that incredibly useful analytical tool.) Yeah: financial and real asset values rise roughly together over the course of decades, but that does nothing to explain or address the stuff economics actually needs to deal with all the time: those very long moments (cf: our present and recent past) where the relation between real and financial asset values is completely out of whack, and wildly variable.

So Kuznets and company…punted: they built their economic model as if we lived in a barter economy. Money (as anything more than a transparent exchange medium like Monopoly money), credit, debt, financial holdings, and wealth accumulations were excluded from — left external to — their model of the economy, as if those things (and their distributions, and the changes in those distributions) were immaterial to the real economy, utterly without import or effect.

They had to do this, because:

1. They wanted to measure and model production of real goods and services, and financial transactions do not generally “produce” anything. But it makes for a problematic model of the economy given that flow of financial transactions dwarfs the real flows in the NIPAs by at least 40 to 1.

2. They had no workable way to think about changes in the quantities and prices of financial assets vis a vis the values of real assets. They didn’t understand money and money-like things. (And in my opinion most or quite possibly all economists still don’t — though I think the MMTers are getting close.)

Given these goals and constraints, how did the Kuznets consortium pull off this feat of modeling/accounting legerdemain? They assumed that S=I — that all the money surpluses generated in a given period are plowed, instantly (or at least within the period), into real investment spending. Even though they’re not. They maintained (and sanctified, codified) the “capital” confution.

And to do that, they had to define Savings not as Income minus Spending, but as Income minus Consumption Spending.

Problem solved. The books balance.

Given the NIPA’s definition of “Savings,” it’s no surprise that “Savings equals Investment.” They set it up that way.

S=I is an ex-ante assumption, adopted by necessity to achieve a particular modeling goal (modeling a barter economy) and work around a particular modeling problem (modeling a financialized monetary economy) — not an a priori Law of Nature.

Update 11/14: I finally crystalized the problem during discussion in comments to this post:

According to the NIPAs, fixed investment is spending, and it is also saving. Contradictory? If I take ten thousand dollars out of the bank to buy ten computers for my employees, is that “saving”?

This is why, in the national accounts, so-called “Savings” is calculated as a residual; it’s not counted/estimated. Estimate Income (using either the Expenditure or Income approach). Subtract Consumption Spending. Voilá! Let’s call that “Savings.”

This is also why both “Income” and “Savings” in the national accounts are unaffected by changes in financial-asset prices — capital gains and losses — and by money/credit/debt/equity issuance and retirement: those are outside the NIPA’s purview, not part of the economy as modeled.

These “money” items are estimated in the Fed Flow of Funds accounts. But even at the Fed, their predictive model includes only one variable (PDF) modeling all these changing concentrations and flows: interest rates.

We can see this definition problem in all the authoritative sources, from Wikipedia to all the textbooks. Here, Krugman:

“They can spend it on consumption,” but spending equals consumption plus investment. Which is right? People can’t spend their income on investment? Does spending include investment spending, or doesn’t it?

Likewise Nick Rowe:

1. Y = C + I + G + X – M

On the left hand side of we’ve got sales of (Canadian) newly-produced final goods (and services) Y. On the right hand side we’ve got purchases of (Canadian) newly-produced final goods (and services), divided up into various categories. Consumption, Investment, Government expenditure, eXports, and iMports.

2. S = Y – T – C

This is a definition of Saving as income from the sale of newly-produced goods minus Taxes (net of transfers, which are like negative taxes because the government gives you money instead of taking it away) minus Consumption.

In 1., purchases (spending) includes investment spending. But in 2., investment spending is not part of spending; it’s not subtracted from sales to calculate savings. Is investment in real assets “spending,” or isn’t it? If a business buys a thousand computers for its employees, doesn’t that diminish its savings for the year?

Bill Mitchell, MMTer extraordinaire, shares the same construct:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Households can’t invest? When businesses invest, it doesn’t reduce their savings?

The apparent assumption behind all this: people only consume (they don’t invest — for instance by building or remodeling homes or starting businesses), and only people save (undistributed business profits are not savings). But that’s certainly not how things are represented in the national accounts. They tally undistributed business profits as savings, and they tally investment by individuals as investment. To me, at least, this is self-contradiction.

I know where some of you are going, by the way: No — business surpluses/profits do not all flow back to households. “Undistributed business profits,” have ranged between 17% and 41% of profits since 1998. (Remember: the NIPAs ignore capital gains.)

In the end you’re faced with this definitional conundrum:

Kuznets says (wisely) that “the real savings of the nation†is real capital — the tangible and intangible stuff that we use to create stuff in the future. — Capital in the American Economy, p. 391.

Wikipedia tells us that national savings is “the amount of remaining money [income] that is not consumed.”

First, money can’t be “consumed” the way goods and services can. They mean “spent on — transferred to others in order to buy — consumption goods and services.” But which is it? Does “national savings” during a period consist of the net flow of money into financial assets (or the net change in the stock of financial assets, including financial-asset market revaluation), or does it consist of money spent to purchase/create real assets? They’re not the same. Really, not even close.

In future posts I’ll be contrasting the Kuznets model to that of ur-MMTer Wynne Godley, and discussing some of the conceptual, practical, political, and normative implications that flow from those models. For the moment I’ll just make the following bald statement:

While this it may not have been Kuznets’ (conscious) intention, the false S=I identity — touted as an unarguable truth — is perhaps the strongest existing intellectual prop for supply-side/trickle-down/Reaganomics/austerian/primacy-of-“capital” economic ideology. Coupled with the faith-based (and also false) notion that the available supply of investment funds is an important constraint on business growth, it’s the crucial foundation for much of the rhetorical infrastructure supporting those ideologies. Those ideologies are built on quicksand — or less charitably, bullshit.

Comments

21 responses to “Savings Equals Investment Equals … Zero?”

Given what some economists have done to truth, reality, and the economy, I don’t care much if I ask/observe/think out loud about stuff which reveals – should I just be wrong – fundamental ignorance and confusion…

So, having made a forced-read through your little essay, and having been following Wray’s little MMT primer, this is a “thought” that came to my mind, further confusing matters I am sure:

Per MMT, banks do not make loans from the deposits they hold. Banks make loans as they simultaneously create assets and liabilities. The limit of any bank’s ability to do this is their capital/equity, as enforced by regulators (who may be honest, or corrupt, or stupid, etc.)

So, then, if banks can fund Investment ex nihilo, so to speak, what real connection is there between Investment and Savings?

I don’t know….but now I wonder just why/how banks bother to pay interest for deposits…

I like this post. Because I like reading people who are really trying to figure things out for themselves, and trying to really understand stuff.

Why *should* we define “saving” as “Y-T-C”? We (economists) define it that way, but we don’t have to. Is this the best way to define it? It’s not obvious that it is.

Here’s a thought-experiment:

An individual spends part of his income on buying land. Is that spending? Is that investment? Is that consumption?

If we define it as consumption, or investment, it doesn’t aggregate up. We can’t all invest in land. Except the Dutch. So we are looking for a definition that works the same at the individual level as at the aggregate level.

Robinson Crusoe doesn’t spend at all. He either consumes the grain he produces, or else saves=invests it for the future.

@Dave Raithel “So, then, if banks can fund Investment ex nihilo, so to speak, what real connection is there between Investment and Savings?”

That’s a darned good question, Dave, one that I’m sad to say I don’t have a cogent answer to. (Hoping other commenters might…) But after I brood on it for several months or years, I hope to. I’m thinking it may have to do with Savings/deposits providing the capital basis which allows the banks to meet regulatory requirements for lending. Maybe nothing more than that?

@Nick Rowe

Thanks, Nick. Welcome words coming from you.

“An individual spends part of his income on buying land. Is that spending? Is that investment? Is that consumption?”

First off, the investment/consumption distinction strikes me as more than a little bit arbitrary; lunch is investment in the afternoon’s work, and fixed capital is consumed during its use. It’s still useful distinction if the terms are clearly defined and understood (I don’t think they are, widely or very well). Just sayin’.

Land: you would land on the one “asset” that I find most perplexing. It seems like a financial asset because like money and other financial assets it can’t be consumed (though its improvements — natural and human-created — can). It certainly acts like a financial asset in our economy. But, unlike financial assets, it actually serves as a means of production. But, unlike other real assets/means of production, it’s not consumed by being used. Also: unlike money and other financial assets, land can’t be created or destroyed, or changed in form — it can only be transferred in exchange for other real and financial assets. I could go on… Maybe somebody has theorized this clearly, cogently, and coherently, but I haven’t come across them.

I think it’s worth pondering all this because so many of the disagreements we see in economics seem to result from people using the same words — even the same mathematical constructs — but meaning different things (with serious emotional, normative, and political baggage attached to those meanings). I’m talking about even everyday words like “savings.” Imagine (made-up idea) physicists arguing about whether an electron is energy without even agreeing what they mean by the word “is” in the sentence. (Sorry, Bill, couldn’t resist.)

“Robinson Crusoe doesn’t spend at all. He either consumes the grain he produces, or else saves=invests it for the future.”

There, you’re saying that saving and investing are synonymous. But if I save *money,* I am ipso facto *not* spending that money on real investment. Back to the barter vs monetary thing? As you’ve said, money is *different.*

Yes: the individual/aggregate issue — individual versus “national” “savings” — seems central to the conceptual difficulty. I’ll keep pondering and reading. Love to hear any more thoughts. Thanks for coming by.

I am not sure what you are trying to prove here – sorry I suspect a muddle.

Take a closed economy.

S_pr – I = G – T

Now G – T is the government’s dissaving or minus of saving. Call it -S_g

so we have

S_pr – I = -S_g or

S_pr + S_g – I = 0

and you have S = I !

“Spending = Income

Spending = Consumption + Investment

Income = Consumption + Investment

Savings = Income – Spending

Savings = (Consumption + Investment) – (Consumption + Investment)

Savings = Zero

So if Savings = Investment, Investment = Zero

Something is really wrong here.”

Well …

The error in consolidating everything.

Take a closed economy with no Government. Divide the economy into three sectors – Households, Production Firms, Banks. Refer to Godley & Lavoie’s Monetary Economics if you like. Only firms do the investment, in this simple model-speak.

S_h = I

h=household

S_allsectors = 0, though. So ?

@Ramanan

Oops. Sorry in that “pr” should have been “h”.

@Ramanan “?”

I don’t have Godley’s Monetary Economics — been waiting for the new edition due in October, meanwhile relying on web-available articles from him:

http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/?auth=104

1. I don’t *think* your arithmetic accounts for undistributed business profits, does it? Again: between 17% and 41% of profits since ’98. Aren’t you assuming that all profits flow to households within the period?

2. Is a model in which only businesses invest very useful for understanding the economy? 50% of the fixed capital stock is residences and improvements — much of it owned by households, with that ownership achieved through 1. investment and 2. capital appreciation.

Assuming the goal is to present a conceptually satisfying/understandable and empirically accurate model of the economy — one that is useful in thinking about and modeling how the economy actually works, I think the solution is to:

1. Redefine “Savings” to mean “change in privately held financial assets.”

2. Remove the notion of “Government Savings.” Just call it Government Deficit/Surplus.

Given these changes, S=I is not an accounting identity — as is proper, given that it’s not true in reality.

This necessarily requires including financial asset flows — including price and quantity changes — in the model that is the national accounts. (This does not preclude estimating real production as part of that model.)

You, Nick, and I all get stuck when it comes to land, though. Like money, it’s *different.* How do you think about it, conceptually, and how do you model it? I really need to think very very hard about that.

Looking forward to going deep into Godley…

@Asymptosis

Asymptosi,

Yes, agreed ignored profits. But if you include profits … divide it into two (unequal parts) – distributed and undistributed. Distributed goes to households and undistributed is undistributed.

The identity then becomes S_h + S_f + S_g – I = 0!

(f=firms)

The question whether this identity tells us anything about how the world needs to be run is an entirely different one.

Talking of Wynne Godley, he was not an “MMTer” btw but his ideas are widely used by the latter.

Asymptosis: “First off, the investment/consumption distinction strikes me as more than a little bit arbitrary; lunch is investment in the afternoon’s work,…”

Yep. I agree. Lunch is a good example. Almost everything a person buys gives a flow of benefits into the future, even lunch. So it’s investment. It’s just that some flows last longer than others. Buying lunch is an investment, if we divide time up in small enough units, but the flow of benefits we get for the next few hours is consumption.

Expenditure on land is usually seen as neither consumption nor investment. It’s not a newly-produced good, so doesn’t count as either. Which is weird at the level of the individual household, but makes sense when we aggregate up, because we can’t all add to our stocks of land (except the Dutch).

To my way of thinking, the important distinction is tripartite: we can spend our disposable income on: 1. newly-produced goods (whether consumption or investment); 2. adding to our stock of money (i.e. not spending it on anything); 3. everything else (buy bonds, land, antique furniture, whatever).

But that way of categorising things makes sense within my theoretical framework, and won’t make sense within other people’s theoretical frameworks. You choose your categories according to what your theory of the world is, and what you are interested in explaining.

@Asymptosis

I don’t know about you, but I sometimes get a sense that I should be freaking out about these social relations and institutions and practices we have somehow developed but don’t really know how they work. Mysteries of nature are awesome, but not really disturbing. But just think about it – banks are everywhere. People leave money with them. But not even the people who own them and run them, nor the economists who study them, can agree on what they do, and how, and what that means with the real economy. Is that not really stupid, or what?

Thanks all for indulging and engaging me on this, apologies for the slower comment pace than elsewhere. Life’s busy.

Another way to explain why I don’t get it:

If you have $100k in income (individual) or profits (firm), what can you do with it?

Spend it (C or I)

Pay taxes

Save it

If you save it, ipso facto, you *don’t* invest it.

So doesn’t Saving = Y – C – I – T? Isn’t that the accurate definition, and isn’t the existing one just plain wrong?

Now redefine Saving again: Y – C – I – T +/- changes in financial assets prices. You get the same MMT-world result (G-T=change in net financial assets), but with a definition of Savings that comports with reality.

Okay, but with existing definitions: if you put it in the bank, don’t they lend it on, and borrower spends it (according to the NIPAs, all on investment)? All within the same period?

No. Obviously not.

S=I assumes instantaneous intermediation (and that all into Investment) — that there’s no expanding and contracting reservoir of financial assets where money can be stored. Hence, since the only way to store money is to lend it (Wray), no credit, debt, or wealth.

Another way of saying it: the NIPAs assume there are no banks. (It might be revealing that in his brave forays into MMT discussions, Scott Sumner is forever bruiting thought experiments in which…there are no banks.)

Clearly, people can and do just sit on their money. In aggregate I think this means that it circulates only in the financial economy — buying and selling things that can’t be consumed — without flowing out in spending, expanding trade in the real economy (which of course is where our surpluses come from).

Nick: “You choose your categories according to what your theory of the world is, and what you are interested in explaining.”

Certainly true. But:

1. I don’t think it’s a question of “choosing” categories; it’s about defining categories, collectively.

2. The Kuznets model is special, because almost every other model takes its categories as givens.

I’m fully aware of how quixotic my effort is here — arguably a fool’s (or a crank’s) quest, but I”m trying to drill down to first principles, which is about accurate starting assumptions/definitions.

And as a first principle/definition/assumption, S=I doesn’t seem to hold water. A monetary economy, ipso facto, has credit, debt, and wealth (monetary “savings” as a stock), and financial intermediation is not instantaneous.

If safe, this obviously would have pretty profound implications for the value of IS-LM (one way of describing Hicks’ reasons for disclaiming it as a “classroom gadget”?), but I fully admit that’s out of my depth.

Yet another way of saying it: S=I assumes something very close to tâtonnement or a Walrasian auction — interesting conceptual constructs, but real-world?

“So doesn’t Saving = Y – C – I – T? Isn’t that the accurate definition, and isn’t the existing one just plain wrong?”

Neither is right nor wrong. It’s just a convention. Some conventions are more useful than others. The conventional definition is S=Y-T-C. Spending on investment goods, bonds, land, used goods, is defined as “saving”.

The conventional definition makes more sense intuitively if you imagine that firms do all the investing, and households lend their saving to firms. Then the investment demand function describes firms’ behaviour, and the consumption function households’ behaviour.

And there are cicumstances under which you can separate the household’s decision into two: how much to consume/save; how much to invest? Which is like splitting the household into two parts, which can make their best choice without knowing what the other part has chosen.

@Nick Rowe

Finally getting a chance to address this with my full mind. Sorry it’s so long, inflicting a great deal of my thinking on you here…. I thought of making it a post but decided to hide my wacky notions in a comment down here instead.

First re: consumption versus investment. I’m not making a big deal of this. Even though orange exists, we can still make a useful distinction between yellow and red. A kudos to the NIPA gang for sorting these out for us as best they can. My key point remains, though: they’re both spending.

Land: understood that the NIPAs treat land purchases like financial-asset purchases, not spending. This makes perfect sense because like financial assets, land doesn’t go away; arguably only the improvements (by man and by nature) can decay or be consumed. I’m still struggling with it because like real assets — drill presses and such — it serves as a means of production. It’s special and different in combining those two attributes.

“Neither is right nor wrong. It’s just a convention.”

I’m probably being starry-eyed, but I’m not satisfied with this.

It seems to me that some conventions are not just more analytically useful; they’re more accurate descriptions of economies, and how they work.

Of course, models are necessary simplifications. The map is not the territory. But suppose the standard mapmakers’ convention was to show roads running along the bottom of lakebeds, rather than going around the lakes (as they actually do)?

Suppose we defined Savings as equaling Consumption — completely at odds with how we understand those words and use those concepts. Would that just be less useful, or is it innaccurate, misrepresentative? We could undoubtedly develop assumptions that would make the bookkeeping work out (all savings are intermediated instantly into consumption spending), but would they be accurate assumptions? We could develop thought experiments that make the definition and associated model more intuitively apprehensible, mentally tractable (businesses only consume; households only invest). We could build elaborate mathematical models based on the definition that give the impression of precision, clarity, and accuracy. But would that make the definition more accurate?

I think S = I, and S = Y – T – C, are exactly those kind of definitions. They don’t correspond to “Savings” as we use the word or understand the concept — or to the way financialized monetary economies actually work.

And I think that speaks to a far more widespread set of failings in economic discourse, even at the highest levels — sloppy, imprecise, vaguely or poorly-defined, ambiguous, even misrepresentative language and concepts. (I *think* this may be an inevitable result of the “equilibrium”-based approach to economics, which I discussed in a comment in the next post. Maybe: It’s impossible to construct coherent concepts and language on top of an inherently problematic base concept.)

Let me go at this from the perspective of a successful business owner. I’ve run a few, from small sole proprietorships to seven figures, and been an equity partner in even larger. Running two little ones right now.

When I buy ten computers for my staff (“invest” in my business), I certainly don’t call that “Saving.” Neither would anyone else (except maybe an economist). It’s the exact opposite of saving (adding to my stock of financial assets). It’s spending (drawing from that stock). That’s at the individual level.

This brings me, in a slight digression, to one of my pet peeves, the sloppy notion of “spending out of income.” It makes sense in a vernacular sense, but to be precise, there’s no way to spend out of a flow. If somebody hands you a five-dollar bill, you can’t spend out of that instantaneous moment of transfer. You can only spend out of the stock that you’ve stuck in your pocket.

This sloppiness matters when you try to think about S and I in aggregate. For S=I to be true at that level, intermediation must be assumed to be instantaneous (within-period). It assumes that the flow of savings does not increase the stock of financial assets or reduce the amount of money circulating in the real economy — that exactly equal amounts flow back out elsewhere. (And that all those outflows go to investment, not consumption.) That whether I withdraw money from the bank to buy ten computers, or refrain from withdrawal, the same amount of money is circulating in the real economy.

Aha! Finally crystalized: I don’t see how you can call the purchase of real assets “spending,” and also call it “saving,” and claim that there’s no contradiction. How useful can a self-contradictory model be?

Likewise “investment” and “capital.” I constantly find economists using the terms without distinguishing between real and financial — as if they were synonymous or in some vague, undefined way, contiguous. (Which they are not — buying/owning computers is not the same as, is exactly the opposite of, making/having a bank deposit/balance — except in aggregate if intermediation is exact and instantaneous.)

I won’t even get started on the “money supply,” which refers to a stock — even though all other “supply” discussions are about flows. (Run don’t walk to read Keen’s Roving Cavaliers of Credit post, which instead talks about flows/increases/decreases in (especially private) money/credit/debt as key movers of economy.)

One of your commenters called you on such a stock/flow confution the other day, and you acknowledged the probable slip. And this (not being obsequious here, just fact) from one of the clearest and most carefully precise economics writers out there. I run into this constantly in economics writing, which makes it frustratingly difficult to understand what’s valid and useful therein, to tease out the important/useful/accurate insights from the resulting muddle (or at least it muddles it in my mind). I run into these stock/flow confutions all the time, sometimes within a single sentence.

I also have a lot of trouble understanding how financial assets can be usefully or accurately treated as “investment goods” or “commodities.”

It seems like there’s a crucial distinction between the two: real goods/commodites/assets can be/are consumed, and they decay. They disappear over time. Financial, synthetic assets can’t, aren’t, and don’t. They can only be created, destroyed, transferred, and (perhaps?) changed in form.

This has me thinking very hard about your thinking re: buying to hold. It seems that all financial asset purchases are buying to hold (and eventually, sell). I think these fundamental differences mean the dynamics of financial markets are qualitatively different from those in real markets. Haven’t sorted out how. (Yet! I’m an eternal optimist.)

Which means that models like IS-LM — which seems to assume that the two types of markets have the same dynamics (and that S=I) — have big problems.

A related confusion: I’m constantly reading stuff from PhD economists (generally when writing in popular opinion venues) saying that the high price of health care, or oil, or taxes is “sucking money out of our economy.” What in the hell does that mean? They don’t seem to have the vaguest notion of what flows and stocks they’re talking about.

If anything “sucks” money out of our (real) economy, it’s saving. (Also, yes, taxation, in a different, MMT sense, and payoffs of private loans — which is saving — and perhaps Fed sales of financial assets from their balance sheet. Haven’t sorted out my thinking on all that.)

Scott Sumner recently responded to one of my comments, saying that he didn’t understand what I meant by “hoarding money” — even though that’s a pretty central concept in Keynes — and that I don’t understand capital (which may be true, though I’m sure trying…).

I say: he doesn’t understand money-hoarding or capital because he assumes that S=I, believes (has he thought about it?), that instant intermediation happens from savings to fixed investment, and thinks that real capital and financial capital, real investment and financial “investment,” purchasing computers and purchasing bonds, are synonymous or at least equivalent.

This is all why I’m so taken with Godley, Keen, and the MMTers. Given the muddled use of words and concepts that (I think) I’m constantly stumbling through in economics writing/thinking, the words “stock-flow consistent” are like hearing angels singing. Hallelujah, at last. (I told you I’m starry eyed.)

I call them them the “bookkeeping-based” school of economics. They start with a chart of accounts that pretty accurately represents the flows and stocks in actual financialized monetary economies, and work up from there via dynamic modeling to see what happens in the modeled world — rather than working down from (static or only contortionately semi-dynamic) assumption-based theories/models. (Rather like climatologists.)

Interestingly, in Godley’s key paper,

http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/1810/225167/1/wp16.pdf

The word “Savings” does not appear. I’m thinking it might not be such a useful or even necessary concept — especially as it’s currently defined.

Oh, also: vis-a-vis financial assets as “goods” or “commodities”: I have a lot of trouble making the “demand for money” idea make sense for me in the normal S/D graph kind of way. I think because the quantity of money produced (“supplied”) is not determined (or very little, in most situations) by its price, but by multiple external factors (Fed decisions, taxing and spending decisions, loan decisions by banks, etc.). These decisions are affected by demand-driven “price” signals only loosely, if at all, and with (often very) long delays.

The potential supply of money is infinite (ultimately, there’s no scarcity), it has (basically) no production costs, and it never decays. So thinking of it as a commodity that has none of those characteristics seems off base. At least confusing to me.

Interesting thread. I would suggest a simple explanation for the confusing land/capital issue, politics.

“Professor Mason Gaffney of the University of California, recently gave us a brilliant expose, in The Corruption of Economics… of the way in which the neo-classical revolution fused land with capital. This conveniently (for the propertied classes) diverted attention from the distinctive treatment of land, in the classical economics of Smith, Ricardo, Mill and Henry George, as a separate factor of production and the natural and prospectively buoyant source of public finance”.

http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/harrisonfred_losses_of_nations_review.html

Likewise, I think the political reason for fusing real investment and financial investment is the issue of capital gains taxation. If policymakers understood that financial investments don’t really do anything (except provide its owner with the psychic equivalent of Scrooge McDuck swimming in his gold coins), they’d be less likely to support lower tax rates on capital gains versus ordinary income. Of course, campaign contributions are what keep them from ever understanding that.

http://www.thomassnow.com/images/scrooge-mcduck.jpg

Instead of a low capital gains tax rate, the better way to incentive real investment is with an investment tax credit (say, 10% of fixed capital spending could be credited against tax bill). And then on the back end, tax at the ordinary progressive rates all income, from whatever source derived.

@beowulf “investment tax credit (say, 10% of fixed capital spending could be credited against tax bill).”

Well right now capital investments by business do come off of taxable profits — they’re spending — though they have to be amortized over the life of the assets. Various measures have been instituted at various times to accelerate or even remove the amortization requirement for various types of investment.

I still prefer the method Milton Friedman proposed: tax business profits as with S Corps: all profits are imputed immediately to the shareholders, whether or not the profits are distributed. (The undistributed profits presumably add to the capital value of the stock, so since they’re being taxed in the year they’re earned, there’s no need to tax them again as cap gains when the stock is sold.)

I’m not sure what he recommended for rates, but I say tax those profits as ordinary income.

This would also remove one of the key rhetorical tools of anti-taxers, the “profits are taxed twice” argument.

Also, the rather obvious aha that I think Mike Kimel came up with: If you tax profits at a higher rate, this provides *more* incentive for businesses to make fixed investments, because that spending comes off taxable profits.

[…] I’m pleased to receive at-least partial support for the notion bruited in my previous post on this topic (“Savings Equals Investment Equals…Zero?”) in comments from Nick […]

Thank you for this post;greatly appreciated. I have been quizzing our Central Bank for weeks on this, with no avail. They reiterate the identity s=i so frequently and with determination as if to convince anyone in earshot. No explanation why it is so. My big question, if s=i, and bank loans are used for i, are bank loans then classified as savings somewhere? And even in a bankless economy, you cannot assume saving and investment intermediation occurs instantaneously in one period. People can keep money under their beds and only spend it in subsequent periods….Surely some dodgy assumptions enter the accounting system somewhere to make this all true…