I’d like to reply to one confusion and one set of pushbacks on yesterday’s post:

Currency and Reserve Balances

I buried one fact: banks can reduce total Fed reserve balances by withdrawing currency — physical cash — from their Fed reserve accounts. I only gestured toward this in a parenthetical and a link. It’s a trivial point for this discussion, but it raises confusion. This is the other thing (besides bonds) that the Fed issues and retires in return for reserve balances. As with bonds, it’s purely an exchange between banks and the Fed (though it’s driven by customers’ cash needs).

Banks actually have nominal control over this. The Fed has to issue currency to them (retiring reserves in exchange) when they ask for it, and they have to retire currency (issuing reserve balances) when banks send it back.

But this in no way suggests that reserve balances are money. You can withdraw currency (notes) from your bank. Does that mean that your checking account contains currency? That checking deposits are currency? No.

This issue is unimportant here because it’s essentially a mechanical function. As long as it’s working properly — ATMs dispense cash and people can deposit cash — it has no effect on things. (And cash is pretty small magnitude in the total system). Banks keep enough cash on hand to handle their customers’ needs, and the Fed accomodates that. Aside from drug dealers, etc., nobody holds much physical currency.

The only reason cash would be an important consideration would be if the Fed starting paying (significant) negative interest on reserve balances — charging the banks to to hold their reserve deposits. Banks might decide to build secure warehouses and drive cash to and from the Fed, trading it for reserve balances, when they needed to fund loans or when loans got paid off. (It’s kinda tricky to fund a $400,000 mortgage with cash…)

Otherwise it’s a nonissue for this discussion. But I should have made it clear.

People really don’t like the idea that the Fed’s not printing “money.” MV=PY adherents especially object.

Let’s look at the standard definitions. None of the monetary aggregate definitions M0 through MZM includes reserve balances. By those definitions, reserves are not money. (Ditto the divisia measures.) So by those definitions, when the Fed issues new reserves, it’s not “printing money.”

The one exception is the “Monetary Base,” or “base money.” That definition of money includes currency, coins, and reserves. Here’s a handy chart from Wikipedia:

| Type of money | M0 | MB | M1 | M2 | M3 | MZM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes and coins in circulation (outside Federal Reserve Banks and the vaults of depository institutions) (currency) | ✓[8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Notes and coins in bank vaults (Vault Cash) | ✓ | |||||

| Federal Reserve Bank credit (required reserves and excess reserves not physically present in banks) | ✓ | |||||

| Traveler’s checks of non-bank issuers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Demand deposits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Other checkable deposits (OCDs), which consist primarily of Negotiable Order of Withdrawal (NOW) accounts at depository institutions and credit union share draft accounts. | ✓[9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Savings deposits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Time deposits less than $100,000 and money-market deposit accounts for individuals | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Large time deposits, institutional money market funds, short-term repurchase and other larger liquid assets[10] | ✓ | |||||

| All money market funds | ✓ |

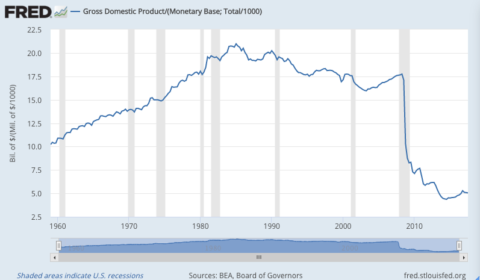

So fine: M in the equation of exchange means Base Money. But if you look at the data using that definition, it seems like there’s some serious explainin’ to do. Here’s the velocity of MB:

A 70+% decline since 2008? Hmm…

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

81 responses to “The Fed Is not Printing Money: Two Updates”

[…] Cross-posted at Asymptosis. […]

Central bank reserves do not circulate in the real economy, right?

“Banks actually have nominal control over this. The Fed has to issue currency to them (retiring reserves in exchange) when they ask for it, and they have to retire currency (issuing reserve balances) when banks send it back.”

Try telling that to Scott Sumner. Plus, aren’t gov’t bonds usually involved there too?

“People really don’t like the idea that the Fed’s not printing “money.†MV=PY adherents especially object.”

What does the scenario look like if the fed buys a bond from a bank, and then the bank buys a bond from Apple?

The “M” in MV is money that can be spent in the economy. Bank reserves = banks’ reserve balances on the Fed spreadsheet and vault cash, neither of which can be spent as such. Equating “M” in MV with bank reserves (rb + vault cash) is therefore inappropriate, since price is not sensitive to the amount of money available but rather to the amount of money tendered. That is to say, money that is saved, e.g., in time accounts, does not contribute as such to effective demand.

The “money” that is available for spending is ordinarily conceived as M1, comprised of demand deposits, other checkable deposits, travelers’ checks, or cash in circulation and that which can be converted to spendable funds easily. The assumption is that money available will be spent but that depends on interest rates and liquidity preference. When liquidity preference is high and rates low, then more funds are saved in demand accounts.

The question is whether M1 is an accurate measure of “spendable money” wrt MV = PT, when, for example, T-bills are highly liquid and can also the best form of collateral.

The “M” in MV is usually conceived as exogenous, but due to banks’ ability to create demand deposits by extending credit, money is actually endogenous. Money created by banks extending credit (loans create deposits), which is limited by customer demand and banks’ capacity and willingness to lend. Banks will not lend to potential customers that are not deemed creditworthy even if they are able. Moreover, those that are best able to borrow will not desire to do so unless they can earn more on the loan than the carrying cost.

So the monetarist approach is flawed on several accounts. First and foremost, money is endogenous rather than exogenous, so the central bank cannot regulate the supply of spendable money, only the size of the monetary base, and there is no causal connection between changes in the MB and M1, that is to say, the money multiplier theory confuses an ex post accounting residual when the cb is using OMO to hit its target rate, rather than an ex ante cause of changes in the amount of bank credit.

Secondly, the cb operates by setting price, i.e., the interest rate, and uses quantity to hit that rate unless it is paying IOR or sets the rate to zero. The theory is that the interest rate influences liquidity preference but t this demonstrably not the case. Interest rates and borrowing are relative to the business cycle, with low rates and low borrowing corresponding to troughs, when demand is low and liquidity preference is high, and high rates and high borrowing to peaks when demand is high and liquidity preference is low.

The monetarist position is based on an amount of loanable funds that is fixed exogenously, so that the interest rate causes changes in relative balance of saving and borrowing, with borrowing corresponding to the level of investment. Where money is endogenous, this does not apply.

@Fed Up

“What does the scenario look like if the fed buys a bond from a bank, and then the bank buys a bond from Apple?”

Nothing that would not happen if the Fed did not buy the bond. The Fed’s buying doesn’t force anyone to sell bonds, although if the price the Fed is willing to pay is higher than market conditions would warrant, this could stimulate sales. But, basically, the bank has an asset it thinks it can exchange for another asset more profitably. The bank doesn’t “sell the bond to the Fed.” The bank sells the bond into the market and the Fed happens to be the buyer. Could have been anyone buying bonds at the time. The bond market is highly liquid and not dependent on Fed buying, in spite of what some may think, although the Fed can affect the yield curve if it chooses to. Even granting the objection for argument’s sake, then the market would clear at a lower bond price and higher yield were the Fed not buying and that would influence the bank’s decision on profitability of holding the US bond or buying the Apple bond.

If the bank decides to sell its bond to buy a new bond from Apple, we know that Apple issued the bonds to fund a dividend instead of drawing down cash. Some of the dividend disbursement will be saved, some will go toward productive investment, and some will be go toward consumption. Investment (other than financial “investment”) and consumption will contribute to aggregate demand. Is this an effect of money policy? Questionable to me.

It seems to me that the transmission mechanism that the Fed is using is the wealth effect, that is, increasing purchases hence prices of risky assets by keeping rates low, decreasing the cost of margin, and making safe assets scarcer by buying tsys and agencies.

@Tom Hickey

“If the bank decides to sell its bond to buy a new bond from Apple, we know that Apple issued the bonds to fund a dividend instead of drawing down cash.”

I don’t think my example was specific enough. The fed buys a gov’t bond from a bank. The bank buys the same type of gov’t bond from Apple. Apple was not issuing bonds. Sorry.

@Tom Hickey

“So the monetarist approach is flawed on several accounts. First and foremost, money is endogenous rather than exogenous, so the central bank cannot regulate the supply of spendable money, only the size of the monetary base, and there is no causal connection between changes in the MB and M1, that is to say, the money multiplier theory confuses an ex post accounting residual when the cb is using OMO to hit its target rate, rather than an ex ante cause of changes in the amount of bank credit.”

I see other people saying there is an accounting identity that states “for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent”. I have a question about that. Let’s say I save $100,000. Someone else wants to start a new bank. They sell me a $100,000 bank bond (bank capital). The reserve requirement is 0%, and the capital requirement is 10%. Can the new bank now make 10 (ten) $100,000 mortgage loans?

Thanks, Steve. I agree my point was “trivial” to your discussion and I apologize for being unable to get thru your whole post. It’s a “weak links” thing. I did not think I was confused however.

TH’s opening paragraph is exceptionally good (meaning, I think I understand it):

The “M†in MV is money that can be spent in the economy. Bank reserves = banks’ reserve balances on the Fed spreadsheet and vault cash, neither of which can be spent as such. Equating “M†in MV with bank reserves (rb + vault cash) is therefore inappropriate, since price is not sensitive to the amount of money available but rather to the amount of money tendered. That is to say, money that is saved, e.g., in time accounts, does not contribute as such to effective demand.

I think of reserves as savings. For me and my bank there may be savings. For my bank and the Fed there are reserves. Neither reserves nor money in savings affects prices, per the TH quote. However, both savings and reserves may be withdrawn, where it becomes spendable and may affect the price level, etc.

Are reserves money? Well, is money in savings money? Same answer to both questions.

@Fed Up

“they will just take everything we have and discard us.” = loanable funds, presupposing exogenous money and a fixed money supply.

Banks fund their assets (loans are assets) many ways, not necessarily through acquiring savings, which is borrowing money from depositors. They can and do fund themselves in the money markets, interbank borrowing and from the cb.

“the capital requirement is 10%. Can the new bank now make 10 (ten) $100,000 mortgage loans?”

Yes, the constraint is the capital requirement and not the reserve requirement since banks regularly fund that requirement with borrowing if they have the opportunity to lend at a profit. Moreover, if necessary to expand lending, they will also add to capital if it deemed profitable.

See “The Inherent Hierarchy of Money” by Perry Mehrling January 25, 2012

http://ieor.columbia.edu/files/seasdepts/industrial-engineering-operations-research/pdf-files/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf

Under a gold standard, gold sits at the top of the hierarchy of money. Absent a gold standard, the apexis high powered money (HPM) aka the monetary base, i.e. bank reserves (reserve balances and vault cash) and currency in circulation.

See also L. Randall Wray, “Money”

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_647.pdf

“Banks promise to convert their demand deposit IOUs to domestic high powered money (currency or reserves at the central bank).” p. 11

“We are now able to answer the question posed above: why would anyone accept

government’s “fiat†currency? Because the government’s HPM (currency plus reserves)

is the main thing (and usually the only thing) accepted by government in payment of

taxes.” p. 13

Banks’ reserve balances can never be spent into the economy as such, since they function as a settlement vehicle in the payments system. However, rb are exchanged with government in settlement of tax liabilities. Generally, taxes are paid by check against a demand deposit. The check is submitted to the Treasury which deposits the check into one of its TT&L accounts, which is marked up, while the reserve account of the customer’s bank is marked down, and Treasury cancels the tax liability. The bank then marks down the customer’s deposit account as the check clears.

The rb received from banks to settle customer tax liabilities is credited to a Treasury account, usually a tax and loan account at a commercial bank. After netting and in coordination with Fed ops, a TT&L account is marked down, withdrawing rb from non-govt, and credit to the TGA to clear future govt spending. The credit to the TGA is not part of bank reserves. Govt spending through the Treasury creates new reserves in non-government by marking up banks’ reserve accounts at the Fed and the corresponding customer deposit accounts. On settlement, the TGA is marked down in the amount of the spending.

So while reserve balances are never used for spending but only for settlement, they are used by the private sector to settle tax obligations with the govt, and people certainly consider that a use of “money.” And they certainly experience an increase in “money” when the government marks up their accounts, e.g., SS. So while they never experience contact with banks’ reserve balances, they do experience the affect on their own accounts in terms of money.

Thus, taxation withdraws money from non-govt by reducing rb or cash, and govt spending creates money in non-govt by increasing rb or adding cash. Govt cash transactions are negligible, however, so this is mostly in terms of changes in rb at the cb.

Conversely, interbank settlement doesn’t create rb unless a bank borrows from the Fed or cashes in vault cash and doesn’t reduce rb unless a bank repays a loan from the cb or exchanges rb for vault cash.

@Fed Up “Central bank reserves do not circulate in the real economy, right?”

Right.

“Try telling that to Scott Sumner.”

Yeah I searched his site for “reflux.” The word doesn’t even appear. Nick Rowe had a post on it that I found to be mainly obfuscatory.

“Plus, aren’t gov’t bonds usually involved there too?”

Not sure what you’re asking. Bonds, currency, and reserves are the three things the Fed can “issue” and “retire” (into and out of the banking system) in exchange for each other.

I uses the quotes because it’s not technically issuing and retiring bonds (there ya go, Ramanan) — just effectively. It is issuing and retiring currency and reserves.

@Fed Up “What does the scenario look like if the fed buys a bond from a bank, and then the bank buys a bond from Apple?”

Effectively, at least (the actual mechanics may be different): the bank sends reserves to apple’s bank, and apple sends the bond to the purchasing bank. No change in total reserves, just a reserve transfer from one bank to another.

@Tom Hickey “Bank reserves = banks’ reserve balances on the Fed spreadsheet and vault cash, neither of which can be spent as such.”

Very important: two different and potentially confusing uses of the word “reserves” here.

“Bank reserves” can include “Reserve Balances” at the Fed (essentially banks’ deposits/credit in their Fed checking accounts), plus other reserve holdings including treasuries and vault cash (and I think gold too).

Those “bank reserves” all count towards required reserves. But they’re not reserve balances/credits/deposits at the Fed, which are the things the Fed can issue, and that we’ve been talking about here.

@Tom Hickey “The question is whether M1 is an accurate measure of “spendable moneyâ€

The question here has been: are reserve balances part of that stock of “spendable money.” The answer, if M1 is your definition, is no.

@Tom Hickey “the money multiplier theory confuses an ex post accounting residual when the cb is using OMO to hit its target rate, rather than an ex ante cause of changes in the amount of bank credit.”

As you can imagine based on my recent posts, I’m really liking that thinking. But can you make it simpler, more crystal clear? What’s the residual, and what’s the accounting identity you’re talking about?

@Tom Hickey

“So while reserve balances are never used for spending but only for settlement, they are used by the private sector to settle tax obligations with the govt, ”

Good to bring this up. Treasury net spending is the other significant way that reserve balances go up and down.

“and people certainly consider that a use of “money.—

Just because that transaction is ultimately resolved at the level of reserve balances doesn’t mean that taxes are “paid with reserves.” All transactions ultimately resolve to the level at reserve balances.

I’m thinking: the “accounting residual” you mentioned is in fact…reserve balances.

They’re a tally of particular account balances, just like capital account balances. Is it in any way useful to say that the U.S. Capital Account Balance is “money”? It’s not crazy to say that, but: 1. it adds zero information or understanding, and 2. it promulgates widespread confusion.

So: yes, when I write a check to Tom, it is essentially a letter to the Fed saying, “please transfer $10 from my bank’s reserve account to Tom’s bank’s reserve account.”

Our banks pass the request on to the Fed.

But I really don’t think you can say that I’m using reserves to pay you or “settle that obligation.” I paid you with bank deposits, and the reserves are just a high-level tally of that transaction.

@The Arthurian “both savings and reserves may be withdrawn, where it becomes spendable and may affect the price level, etc.”

There, I think, we’re seeing a wrong assertion of causation. It’s the very assertion that monetarists make.

You withdraw cash from the bank because you want to spend it.

You don’t spend it because you chose to withdraw it.

(Don’t tell anyone but) I keep a good-sized chunk of cash hidden away to avoid ATM fees. (Yeah, I’m a cheap bastard…) This has exactly zero effect on how much I spend.

Alternately, I could have kept that money “in the bank.” At the ultimate level of accounting resolution, you could say that I was holding it in Fed reserve balances. Again, that decision would have exactly zero impact on how much I spend.

It’s necessary to realize there there are several things going on where monetary transactions are involved that need to be distinguished. First, the monetary economy in a particular currency is a closed system in that only the government is authorized issue the currency. In modern economies, “money” is conceived of in terms of the currency as “state money,” which is issued by the Treasury or the central bank — with central banks now predominating in currency issuance and Treasuries chiefly issuing government securities.

Currency and Treasury securities are issued into non-government through the national banking sector, which is a public-private “partnership,” not in equity but operation in that govt charters, regulates, and oversees the banking sector, operates the payments system, and otherwise maintains “good order.”

So within the closed monetary system of a currency zone with a central bank at the apex, there are two principal subsystems that are open to each other, government and non-government as the consolidated domestic private sector and the external sector. That is to say, there are essentially two systems — government and non-government, — and the interface, through which they interact, which is the central bank and Treasury wrt monetary affairs.

Government establishes the unit of account in terms of its currency. In the US, the term “dollar” is used for both the currency and the unit of account. In China, the RMB is the currency and the yuan is the unit of account. The non-government system uses the currency as unit of account in pricing and a medium of exchange in transactions, and records transactions in the unit of account. The government system uses the currency as a unit of account and a medium of exchange with non-government, but only as the unit of account within government.

That is to say, there are no monetary exchanges within government and no market. The government’s consolidated books are just accounting entries recording transfers among government entities in the course of operations. As Warren Mosler says, as the currency issuer through either its Treasury or central bank, the government neither has nor does not have “money.” Government injects money into the non-government system through spending and transfers, withdraws money through taxes, and provides default risk free assets in the form of govt securities as consolidated non-government net financial assets in aggregate.

These form the basis of the modern monetary system, over which government holds a monopoly wrt its currency — in the US iaw US Const, art 1, sec 8, 10 — and it can exercise this monopoly by setting price, e.g., the interest rate and the prices it pays for goods obtained in markets, regulating quantity as the cb does wrt to rb when using OMO to hit its target rate, and also by delegating money creation the banking sector and regulating financial sector.

This means that what we call “money” is a highly complex phenomenon in a modern monetary economy, so that using the term “money” in any sort of technical sense is fraught with ambiguity. In order to avoid confusion, this requires specifying precisely what one means and this generally means knowing how these interfacing systems operate and where entries show up on the books of the counterparties in double-entry. Without being clear on this, confusion is like to result and stock-flow consistency impossible to achieve.

So I would say that when people use “money” in a discussion about economics, especially monetary economics, they should be asked to specify exactly what they mean by this. I am not an economist but a philosopher and contemporary Anglo-American philosophy is dominated by logic and linguistic analysis. Ludwig Wittgenstein is famous for observing that philosophical problems turn out on analysis to be pseudoproblems arising from failure to under the logic of the language. This same criticism can be applied to many of the issues that arise in economics, especially when “money” is involved, which in a modern economy is just about always since important data are reported in terms of monetary value in the unit of account. Therefore, understanding the operations of the monetary system and stock-flow consistent modeling are the sine qua non of contemporary theoretical economics and political economy (economic policy). Post Keynesians get this. Others, not so much. I have attempted to bring up these issues with some monetarists, to little avail.

you could say that I was holding it in Fed reserve balances.

Actually, no one is “holding money” in their deposit account. They have lent to the bank which generally borrows to fund its LHS instead of increasing equity.

Reserve balances are assets of the bank held at the cb, hence are risk free for the bank. However, deposit accounts are money lent, hence at risk.

That risk is absolved up to a point by government guarantees such as provided by the FDIC in the US. Above that point, the funds are at risk, which is a reason that firms, funds, etc, use government securities instead of large deposit accounts.

“(Don’t tell anyone but)”

hidden in the hollowed out buttocks of an action figure, maybe?

Pssst, I didn’t say anything about causation. If you want to spend it, but you have to withdraw it before it is available, then you withdraw it, and then it is spendable.

@Tom Hickey “So I would say that when people use “money” in a discussion about economics, especially monetary economics, they should be asked to specify exactly what they mean by this.”

This exactly my point:

Since nobody ever does define it — they almost always use the vaguely and imprecisely — they should stop using the word.

They should talk about currency, or Fed reserve balances, or bank deposits, or whatever.

Instead of defining “money” every time as X or Y or X+Y or whatever, just say X or Y. Pretty simple.

@Tom Hickey

About the new bank, I saved $100,000. I lent $100,000 to the bank, and the bank borrowed $100,000. The bank lent $1,000,000 to ten other people, and the ten other people borrowed $1,000,000. The bank lent $1,000,000 to ten other people, however, it only borrowed $100,000 from me.

Is that scenario correct? If so, for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent just got violated. So …

Is for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent wrong?

Does for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent need some kind of adjustment?

Is there something wrong with my scenario?

@Tom Hickey

What I run into is that for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent means only the central bank can increase the money supply. Then they say the money supply = MOA = monetary base = currency plus central bank reserves.

@Tom Hickey

“”they will just take everything we have and discard us.†= loanable funds, presupposing exogenous money and a fixed money supply.”

What do you think of the idea that “loanable funds” is a 100% capital requirement?

In an endogenous system the cb adjusts the quantity of reserves to provide for settlement and support the policy rate when it doesn’t wish to set the rate to zero or pay IOR. So the amount of reserves equal to the reserve requirement is a residual of cb operations in supporting the policy rate. The cb doesn’t want to force banks to pay the discount rate by providing to few reserves nor does it want to allow the rate to fall below the policy rate by providing excess reserves that would drive the rate below its target. Thus the residual is a result of the cb’s monetary operations in setting the policy rate above zero without paying IOR.

When the cb wants to set the rate above zero and not pay IOR, then excess reserves will drive the interbank rate down and make it difficult to impossible for the cb to hit its target rate. So it has to use coordinated ops with Treasury as well as OMO to limit excess reserves to a quantity that allows for settlement while supporting the policy rate the cb desires. This means that as a result of these operations, reserve balance stay close to the reserve requirement.

So the cb announces the target rate, FFR in the US, and then adjusts the quantity of reserves in order to hit that rate. Therefore, if the reserve requirement is 10%, then the quantity of reserves that the cb makes available through its operations will reflect this.

The availability of reserves as monetary base has nothing to do with banks ability or willingness to lend, since the cb expand and contracts the MB as needed to support the endogenous nature of money, including acting as the lender of last resort to ensure clearing. If banks increase lending, then the cb will increase the quantity of rb to provide for settlement while meeting the reserve requirement and supporting the policy rate. If less, then the cb will decrease the quantity to reduce excess reserves that would drive the rate below what the cb desires.

Thus, there is no causal transmission mechanism linking the monetary base and bank lending, as the money multiplier assumes. Now that the Fed is paying IOR and doesn’t need to manage quantity of reserves, it has become clear that the quantity of excess reserves does not influence bank lending in the way the money multiplier assumes.

The point is that reserves function as a settlement vehicle in the payments system, and whatever type of interest rate setting operation the cb undertakes, it will always ensure that there are enough reserves available for the system to clear. If the cb chooses not to set the rate to zero and doesn’t wish to pay IOR, then the quantity of excess reserves has be to kept in line with the reserve requirement if the system is to clear within the range of the policy rate that the cb sets, e.g., between the discount rate and the target rate.

@Asymptosis

“”Try telling that to Scott Sumner.â€

Yeah I searched his site for “reflux.†The word doesn’t even appear. Nick Rowe had a post on it that I found to be mainly obfuscatory.”

Try here:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=20433

I believe he starts with cannot and then eventually goes to want to.

“I’ve recently done a number of posts explaining how monetary policy impacts prices in the long run. The basic approach might be called the “hot potato model.†People have a certain demand for non-interest bearing money. When the Fed increases the supply of base money, people try to get rid of excess cash balances. Individually they can do so, but collectively they cannot. The paradox is resolved by the fact that when people try to get rid of excess cash balances, prices rise until the public wants to hold those extra cash balances.”

Later, “Mike, Whenever the supply of something rises its value will fall, unless offset by changes in other assets that are perfect substitutes. But there are no perfect substitutes for cash, and most substitutes aren’t even particularly close. That’s why unexpected OMOs have such a big effect on markets–they lead to changes in the value of base money.

It’s true that the public COULD fully offset the effect of an OMP by holding more of their M1 in the form of DDs and less in the form of cash, but why would they WANT TO?”

Easy answer. They want to continue saving (not spend on C goods and not spend on I goods in the present).

$1,000,000 to ten other people

The bank now has loans (assets) on the LHS totaling $1,000,000 that it has to fund on the RHS with borrowing or equity and a reserve requirement of 10% to meet, as well as the capital requirement. If the originally saved $100,000 is retained as deposit, it would go toward the LHS funding.

The original deposit of whatever doesn’t figure in the bank’s ability or willingness to lend because banks don’t lend out either saving or reserves and they don’t lend against savings for reserves. The lend against capital and have to fund the LHS with the RHS as a matter of double entry.

Where the “$ borrowed is $ lent” is true is that the depositor lends the bank a sum, which the bank borrows, and where the bank lends by creating a deposit based on borrowing rather than lending. But that says nothing more than that there is a double entry on both parties books.

“What I run into is that for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent means only the central bank can increase the money supply. Then they say the money supply = MOA = monetary base = currency plus central bank reserves.”

They confuse the MB with “money supply” as in MV=PT, which is wrong since the bank reserve component of the MB is not spendable absent banks lending into the economy. As we see with payment of IOR, there is no correlation of the size of the MB with “M” in MV=PT, in other words, the expansion of the MB through has not resulted in a rise in goods prices as the theory would predict. It’s wrong and we know why it is wrong.

Even if the MB were composed completely of currency in circulation, that doesn’t constitute a cause of spending because it is not true that money burns holes in pockets. If liquidity preference is high due to economic conditions, those funds will be saved regardless of the form in which they are held.

It’s pushing on a string.

“What do you think of the idea that “loanable funds†is a 100% capital requirement?”

A 100% capital requirement just makes borrowing more expensive and banking less profitable. It doesn’t result in a fixed money stock.

Under a gold standard and no cb as lender of last resort, a 100% reserve requirement with a fixed amount of gold reserve would result in a constant money supply.Then banks would have to own or borrow in terms of a fixed amount of gold in which gold is rival and exclusionary.

In a bullion system, which some now advocate, this would involve holding actual gold, while under a gold standard gold certificates could be used instead of bullion but they would be limited in amount to the gold reserves into which they would be convertible on demand. Others advocate this system rather than a bullion system, which they see as less practical. In both cases there is no cb and no fractional reserve lending. The interest rate would be set endogenously by the market based on liquidity preference rather than exogenously by government through the cb.

@Fed Up

“Easy answer. They want to continue saving (not spend on C goods and not spend on I goods in the present).”

Right, the error arises from the erroneous assumption Say made that those who receive money immediately wish to rid themselves of it since the value of money is instable, i.e., there is no saving, hence no demand leakage to saving.

@Asymptosis

Doesn’t Apple end up with some demand deposits too?

@Tom Hickey

“The original deposit of whatever doesn’t figure in the bank’s ability or willingness to lend because banks don’t lend out either saving or reserves and they don’t lend against savings for reserves. The lend against capital and have to fund the LHS with the RHS as a matter of double entry.”

If the $100,000 is currency, I think it could affect the bank’s ability to lend. Depositing $100,000 in currency into the new bank to a checking account would lower the fed funds rate if the fed did nothing. If there was enough bank capital and credit worthy borrowers who want to borrow then $1,000,000 in demand deposits could be created before the fed funds rate would start rising. If the $100,000 is demand deposits, then depositing them into the new bank to a checking account would not affect the fed funds rate systemwide.

@Tom Hickey

“They confuse the MB with “money supply†as in MV=PT, which is wrong since the bank reserve component of the MB is not spendable absent banks lending into the economy.”

What I see is they want to “force” the conversion of central bank reserves to currency and then get that amount plus vault cash into the economy. They basically are trying to ignore how demand deposits work in the economy.

They think this is not possible or would not occur for some reason. $800 billion in currency, $2.2 trillion in central bank reserves, $6.2 trillion in demand deposits. The $800 billion circulates, $3.2 trillion in demand deposits circulates, and $3.0 trillion is saved in demand deposits. Do something (like take IOR negative). Now there is $4.0 trillion in currency circulating and $3.0 trillion in currency saved. Not much has changed. These other people see currency went from $800 billion to $7.0 trillion and are all excited by that extra “M being created”.

@Tom Hickey

“A 100% capital requirement just makes borrowing more expensive and banking less profitable. It doesn’t result in a fixed money stock.”

It seems to me it does fix the MOE/MOA supply. When doing some accounting, I get $ saved = $ dissaved 1 to 1.

@Tom Hickey

“Where the “$ borrowed is $ lent†is true is that the depositor lends the bank a sum, which the bank borrows, and where the bank lends by creating a deposit based on borrowing rather than lending. But that says nothing more than that there is a double entry on both parties books.”

That sounds like somewhere “for every $1 borrowed there’s $1 lent” may be not true. If so, it is not an accounting identity?

I’m trying to figure out if this is an accounting identity or not. If it is, what modificiation needs to be made to make my example work in accounting terms.

@Tom Hickey

“The original deposit of whatever doesn’t figure in the bank’s ability or willingness to lend because banks don’t lend out either saving or reserves and they don’t lend against savings for reserves. The lend against capital and have to fund the LHS with the RHS as a matter of double entry.”

I think the original deposit matters because my savings in the MOE/MOA got allocated to bank capital. That means it is bank capital that gets lent against.

Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and equity new bank = $100,000 bank bond

The loans get made.

Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and $1,000,000 in loans, liabilities new bank = $1,000,000 in demand deposits, and equity new bank = $100,000 bank bond

@Fed Up

The FFR is set by the Fed and the Fed has the means to hit the target rate regardless of what happens in banks. The FFR is the rate announced by the Fed as its target. The discount or penalty rate that sets the ceiling is also a rate that is set and announced.

If paying IOR, then then Fed sets uses the rate it pays iaw its target, and if the Fed is not paying IOR, then it uses OMO to adjust rb quantity to hit the target rate. The interest rate is not a rate that is set by the market. The FOMC is a command system.

@Fed Up

“What I see is they want to “force†the conversion of central bank reserves to currency and then get that amount plus vault cash into the economy.”

No way to force this. Banks hold vault cash based on expected window demand. They earn no interest on vault cash.

There is some thinking that setting a negative interest rate would force banks to hold vault cash and that would induce lending. Again, no transmission mechanism. Banks don’t lend “because they have money.” They lend because there is demand from creditworthy customers, and then the fund the loan the least expensive way they can.

@Fed Up

“It seems to me it does fix the MOE/MOA supply. When doing some accounting, I get $ saved = $ dissaved 1 to 1.”

As Warren Mosler, who has been a principal in a bank, points out, a 100% capital requirement is lending your own money and that is not banking. There would be money lenders at high interest perhaps, but not banks as we know them. Banking is only profitable on leveraging capital.

What would happen is that shadow banking would expand to fill the gap.

When the bank lends it has to fund the loan, which appears on the LHS of the balance sheet, with an entry on the RHS, which means either from borrowing or with equity. Banks borrow to fund loans by taking deposits and borrowing in the money market.

Banks fund required reserves and reserves for settlement the same way, since this borrowing is reflected in the bank’s reserve account at the Fed — although they can also borrow from Fed temporarily via repo and at the discount window.

@Fed Up

“I think the original deposit matters because my savings in the MOE/MOA got allocated to bank capital. That means it is bank capital that gets lent against.”

The deposit is booked as a liability and remains a liability until cancelled by withdrawal. If the bank decides to increase its capital that is an entirely separate matter. Banks don’t increase capital based on receiving deposits. There is no inherent connection between “your savings” and whatever the bank does in its other operations.

@Tom Hickey

That is why I said if the fed does nothing. Ignoring a step or so, the fed can sell a bond to the bank for the currency so the fed funds rate stays on target.

@Tom Hickey

They will say it is not about inducing lending. It is about converting central bank reserves to currency (no lending involved) and having people withdraw the currency. Their idea of “M in circulation†goes to $3.0 trillion from $800 billion. They will say that extra “M†will mean more spending.

@Tom Hickey

From what I can tell the people who say for every borrower there is a lender, “for every $1 borrowed, there’s $1 lentâ€, or banks are only financial intermediaries mean “lending your own money†(a 100% capital requirement). Think lending to a friend.

@Tom Hickey

“Banks don’t increase capital based on receiving deposits. ”

I think they can increase bank capital by receiving demand deposits or currency (it matters how demand deposits and currency are deposited at a bank). From the example above,

Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and equity new bank = $100,000 bank bond

The assets could be demand deposits too.

Putting the $100,000 into a checking account would be different.

@Tom Hickey

Let’s say I save $100,000. Someone else wants to start a new bank. They sell me a $100,000 bank bond (bank capital). The reserve requirement is 0%, and the capital requirement is 10%. Can the new bank now make 10 (ten) $100,000 mortgage loans?

Yes.

About the new bank, I saved $100,000. I lent $100,000 to the bank, and the bank borrowed $100,000. The bank lent $1,000,000 to ten other people, and the ten other people borrowed $1,000,000. The bank lent $1,000,000 to ten other people, however, it only borrowed $100,000 from me.

That scenario seem correct to me.

At the very beginning, I don’t think the bank had to “fund itself” (the $1,000,000 in demand deposits were created “out of thin air”). Let’s try to keep this simple. A home builder owned the 10 homes and sold them for $100,000 each. It decided to open account(s) at the new bank. So 10 accounts at the new bank were marked up and then marked down by $100,000 each, while the home builder’s account was marked up by the $1,000,000.

The home builder allocates as follows:

$500,000 in a savings account and $500,000 in a 5 year CD. Bank is funded now?

All these things are hypothetical based on ignoring that banks are profit-seeking firms that operate in a highly technical way, and the cb’s function is to make sure that the system always works, stepping in to support it if needed. They leverage their capital and make their money (from banking operations) of the spread they charge using risk management. The cb influences the spread by setting the interest rate, which determines the cost of capital (prime rate). Risk management is handled through the loan officers, and asset-liability management through the ALM department. Bank’s try to minimize capital to maximize leverage, since the amount of leverage influences the profitability of lending.

I don’t think that the $100,000 the bank borrows against a bond counts to bank capital since the $100,000 received is booked as an asset, and there is an equal liability against it. So there is no equity involved. Bank capital is assets minus liabilities, but there is a weighting system, too, with different tiers of capital.

The 1mil loans appear on the LHS of the balance have to be funded by 1 mil on the RHS. This changes in the course of bank ops, e.g., deposits come and go, and it is the business of the ALM department to handle the funding ops as inexpensively as possible considering maturity transformation. For example, short term is least expensive but most risky.

How does the currency get from vault cash to cash withdrawals without passing through deposit accounts? If they are existing deposit accounts, more vault cash doesn’t result in more withdrawals. If they are new deposit accounts then they were opened by people who want to park funds instead of spending, or they are created by lending.

There is no transmission mechanism.

For every borrower there is a lender just means that credit extension by one party implies debt assumption by another. These are entries on books. When a bank lends it credits a deposit account in the amount of the loan as a liability on its balance sheet, and it promises to either provide cash at the window on demand or to clears drafts on the account when made. Until withdrawn, the deposit (RHS) funds the loan (LHS). As the deposit account is drawn down, the bank has to seek other funding, which is the responsibility of ALM. It can attract other deposits, borrow from other banks, borrow in the money market, or from the cb using repo.

The notion that banks are intermediaries between borrowers and savers is somewhat the case, e. g., consolidating the entire banking system as one institution, but the fact that the cb is in the picture as lender changes the picture, too. Yet, it is is true that for the most part, excluding the role of bank equity and cb lending, banks make money by borrowing low and lending high, that is, from the spread they charge. But it is not the case that there is an amount of loanable funds that is determined by the amount saved, since banks can also borrow from the cb.

A 100% capital requirement is bank’s lending against 100% equity (assets minus liabilities, with weighted tiers of capital). Deposits held by the bank are liabilities.

@Tom Hickey

Cancel the above. I did not quote Fed Up correctly and mixed his comment with mine. I’ll redo it.

The money that banks receive from depositors, whether created by the bank making a loan, or marking up a deposit account from receiving a check, electronic transfer, or cash, counts as a liability on the bank’s balance sheet and therefore doesn’t add to bank capital.

@Tom Hickey

I believe the bank bond could be considered bank capital, depending on the circumstances. I was trying to use a bond for “for every $1 borrowed, there’s $1 lentâ€. I didn’t want to get into the difference between a bond and a stock. The example could be run with the new bank issuing stock. Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and equity new bank = $100,000 bank stock. At the very beginning, I don’t think the bank had to “fund itself†(the $1,000,000 in demand deposits were created “out of thin airâ€). See my #47 comment.

@Tom Hickey

Negative IOR means banks will charge for checking accounts, savings accounts, and CD’s. People will withdraw the currency.

@Tom Hickey

Here is a sample of what I see at other places.

Who are we all borrowing from? The Martians? Though when it comes to banks, we are, in aggregate, borrowing from ourselves. Because there are two sides to a bank’s balance sheet. When we both lend to banks and borrow from banks, we are converting illiquid into liquid (monetary) assets and liabilities. Someone has both a mortgage (where he borrows from the bank), and a checking account (where he lends to the bank). It is as if he lends to himself, via an intermediary.

To which I say:

Assets new bank $100,000 in currency and equity new bank = $100,000 in bank stock

Assets new bank $100,000 in currency and $1,000,000 in loans. Liabilities new bank = $1,000,000 in demand deposits and equity new bank = $100,000 in bank stock

$100,000 in currency became $1,000,000 in demand deposits. To me that means $ borrowed not equal $ lent going back to bank capital = bank bond, depending on the definitions of borrowed and lent.

My understanding is that bank capital is equity — assets minus liabilities. A bond issued by the bank is a bank liability. So it has an asset realized from the sale of the bond and a liability against the bond, netting to zero.

I am not on how bank capital is figured, and it is possible that long term debt is figured differently. But I don’t have time to look it up.

Whatever, the bank is permitted to loan up to the limit of the capital requirement. But it is not a simple as that, I understand, since risk is balanced against reward. So banks leave leeway for loses.

Yes, but if they want to save they won’t necessarily spend it. They will find other ways to save like bonds, equities, etc. so it unlikely to increase nominal aggregate demand, just drive risky assets higher than they would be otherwise. You can make people spend when they want to save.

@Tom Hickey

I probably won’t say this right the first time but…

Currency and/or demand deposits that get “deposited†in a customer’s account of a bank become liabilities of the bank, while currency and/or demand deposits that get “deposited†in the bank’s account of that same bank become assets of the bank.

For example, selling new bank stock means that the currency and/or demand deposits become assets of the bank (bank capital) because they get “deposited” in the bank’s account not a customer’s account.

[…] Update 5/21: See two updates to this post here. […]

@Tom Hickey

In the negative IOR case, people can buy goods/services with currency, financial assets with currency, or just hold it.

Some people don’t understand the last two are possible.

Tom Hickey, what do you think of my comment at @Fed Up 56 ?

Assets

100,000 cash (contribution from sale of shares)

1,000,000 loans outstanding

Liabilties

100,000 equity

1,000,000 funding of loans through borrowing (initially from deposits created by the loans)

As the deposits created by lending are drawn down, the bank has to obtain other funding from either equity or borrowing to balance the LHS and RHS. This is the job of ALM. Equity infusion from sale of shares and borrowing in the private sector has to come from someone’s saving. Depending on liquidity preference of the private sector along with the policy rate, banks will have to pay more or less interest to attract deposits or to borrow in the money market for the funding.

Right.

“Currency and/or demand deposits that get “deposited†in a customer’s account of a bank become liabilities of the bank”

Yes, they are credited to the customer’s deposit account which is a liability of the bank. The bank is borrowing from the customer (saver).

“currency and/or demand deposits that get “deposited†in the bank’s account of that same bank become assets of the bank.”

Yes. If the bank sells equity, then it receives either currency that is debited to its cash account (asset of the bank) or a bank check, which results in a credit to its reserve account, which is also an asset of the bank — LHS. Since there is no liability associated with it it shows up as equity on the RHS.

If the bank sells a bond, it receives an asset equal to the sale price of the bond that increases the bank’s LHS, which is funded in a liability account on the RHS.

The $100,000 received for shares is booked on the LHS and equity correspondingly increased on the RHS. (no borrowing, but the $ is someone’s saving)

$1,000,000 lending is booked on the LHS as a “receivable” in a loan account (asset), and on the RHS as a “payable” in a deposit account (liability). As the deposit accounts are drawn down, the bank has to fund the loans outstanding as assets on the LHS through either borrowing (liability) or equity on the RHS to bring LHS and RHS into balance.

@Fed Up “When the Fed increases the supply of base money, people try to get rid of excess cash balances. Individually they can do so, but collectively they cannot.”

Where he’s wrong: they can collectively get rid of those cash balances by…paying off debt. Voila.

His use of “base money” is completely specious here: base money doesn’t include bank deposits — only coins, currency and reserve balances.

@Tom Hickey

“If the bank sells a bond, it receives an asset equal to the sale price of the bond that increases the bank’s LHS, which is funded in a liability account on the RHS.”

I think it could go into capital. I found these here:

http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128b.pdf

“Part 2 presents the calculation of the total minimum capital requirements for credit,

market and operational risk. The capital ratio is calculated using the definition of regulatory

capital and risk-weighted assets. The total capital ratio must be no lower than 8%. Tier 2

capital is limited to 100% of Tier 1 capital.”

“The Committee has therefore concluded that capital, for supervisory purposes,

should be defined in two tiers in a way which will have the effect of requiring at least 50% of a bank’s capital base to consist of a core element comprised of equity capital and published reserves from post-tax retained earnings (Tier 1). The other elements of capital

(supplementary capital) will be admitted into Tier 2 limited to 100% of Tier 1.”

“The Committee is agreed that subordinated term debt instruments have significant

deficiencies as constituents of capital in view of their fixed maturity and inability to absorb

losses except in a liquidation. These deficiencies justify an additional restriction on the

amount of such debt capital which is eligible for inclusion within the capital base.

Consequently, it has been concluded that subordinated term debt instruments with a

minimum original term to maturity of over five years may be included within the

supplementary elements of capital, but only to a maximum of 50% of the core capital element and subject to adequate amortisation arrangements.”

@Tom Hickey

“The $100,000 received for shares is booked on the LHS and equity correspondingly increased on the RHS. (no borrowing, but the $ is someone’s saving)”

MOE/MOA in circulation went down by $100,000 (saved).

“$1,000,000 lending is booked on the LHS as a “receivable†in a loan account (asset), and on the RHS as a “payable†in a deposit account (liability). As the deposit accounts are drawn down,”

MOE/MOA went up by $1,000,000. When that $1,000,000 is spent on the houses (dissaved), it starts circulating.

Overall, MOE/MOA in circulation went down by $100,000 and then went up by $1,000,000. Notice the $900,000 increase of MOE/MOA in circulation.

@Fed Up

“I think it could go into capital.”

Apparently so, but not at full value.

@Asymptosis

“His use of “base money†is completely specious here: base money doesn’t include bank deposits — only coins, currency and reserve balances.”

I think he will say demand deposits don’t matter because for every borrower, there is a lender or for every $1 borrowed, there’s $1 lent. No change in “money”. Only the central bank can increase “money”.

“Where he’s wrong: they can collectively get rid of those cash balances by…paying off debt. Voila.”

I think he will say for every borrower, there is a lender or for every $1 borrowed, there’s $1 lent. If someone pays off debt, just get/force the saver to spend.

See why it is important to show that for every borrower, there is a lender and/or for every $1 borrowed, there’s $1 lent is/are false. That eliminates such nonsense.

Right, the $1,000,000 borrowed by contractors on the $100,000 invested in bank equity is invested in new construction, based on the bank leveraging its capital. The bank makes a (gross) profit on the spread between the interest on the loan and the cost of funding it.

@Tom Hickey

I was thinking more along the lines that workers would be the ones borrowing the $1,000,000 (ten $100,000 mortgages) to buy the houses and that the $100,000 in currency or demand deposits would sit in the bank’s account somewhere with a velocity of zero.

@Tom Hickey

The way I read it (not sure if it is correct) and using my example.

Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and capital new bank = $100,000 of bank stock

The new bank can now issue up to $50,000 of bank bond(s) as bank capital.

Assets new bank = $150,000 in currency and capital new bank = $100,000 of bank stock and $50,000 in bank bond(s)

@Fed Up

More likely the bank would not hold the $100,000 at no interest. Probably would put it into govt bonds. Then the bank can use the bonds for repo collateral, too.

I believe the capital requirement applies only to making loans, not issuing bonds. The bank can just sell long term debt, say $100,000, if it decides to raise capital that way instead of selling more shares. If the the principal is weighted as bank capital at 50% of face value, then the bank has a capital base of another $50,000 for a total of $150,000 to leverage based on the capital requirement.

@Tom Hickey

JKH usually tells me the same thing about gov’t bonds. What maturity/ies can be bought? I’m thinking of the current scenario. I believe 2 year gov’t bonds yield .22% while the fed is paying IOR of .25%. That means the new bank will exchange the currency for central bank reserves at the fed and mark up its checking account. The currency at the fed has a zero velocity in the real economy, and the demand deposit of the new bank will have a zero velocity in the real economy.

Sound good?

@Tom Hickey

“If the the principal is weighted as bank capital at 50% of face value”

From my #67 comment, “but only to a maximum of 50% of the core capital element”. It is saying core capital element not face value. For example,

Assets new bank = $100,000 in currency and capital new bank = $100,000 of bank stock

The new bank now issues $300,000 of bank bond(s).

Assets new bank = $400,000 in currency and capital new bank = $100,000 of bank stock and $50,000 in bank bond(s) plus liabilities new bank = $250,000 in bank bond(s)

It is not “and $150,000 in bank bond(s) plus liabilities new bank = $150,000 in bank bond(s)”

That is the way I read it.

At the moment, apparently due to high liquidity preference, banks are just leaving funds as rb, on which the Fed is now paying IOR instead of holding T-bills, which would be normal.

Banks naturally seek to maximize risk weighted return consistent with other operational considerations like liquidity. Whatever, over the past several years, since the Fed began paying IOR, the proceeds of QE bond purchases by the Fed are sitting in bank’s reserve accounts at the Fed, swelling the MB.

“That means the new bank will exchange the currency for central bank reserves at the fed and mark up its checking account. The currency at the fed has a zero velocity in the real economy, and the demand deposit of the new bank will have a zero velocity in the real economy.”

When the bank decides to reduce its cash currency, it exchanges it for reserve balances at the Fed, i.e., exchanges one type of bank asset for another. The Fed marks up its currency account and marks down reserves, both currency and reserves being Fed liabilities. Currency and reserves are equivalents at the Fed.

Velocity as in MV=PT applies only to spendable money, and that measured by M1 — currency in circulation outside of bank vaults, demand accounts and other checkable deposits, and travelers’ checks.

@Fed Up

That’s a question for JKH. I am not familiar with the rules having to do with bank capital.