Upate: Those who have qualms about the methodology and underlying assumptions here would do well to consider Thomas Piketty’s thinking on page 210 of Capital in the 21st Century. He distinguishes between “real” and “nominal” assets, pointing out that real asset values climb along with inflation and growth, while nominal asset values don’t.

A simple rule of economic arithmetic that economists seem to studiously ignore:

Inflation transfers real buying power from creditors to debtors, with nary an account transfer visible anywhere on anyone’s account books. Inflation means that debtors pay off their loans over time with less-valuable dollars — dollars that can’t buy as much bread, butter, and guns.*

Higher inflation causes, is, a massive transfer from creditors to debtors.**

And the Fed is run by creditors. Inflation is, always and everywhere, very very bad for them.

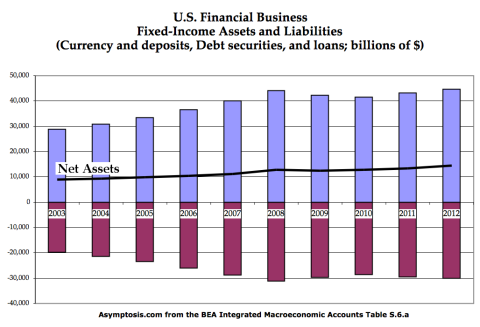

How bad? Look at the fixed-income assets and liabilities of financial corporations:

Financial businesses are net creditors to the tune of $9-$14 trillion dollars.

If inflation was 1% higher than it is, it would transfer between $90 and $140 billion dollars to their debtors. Every year. For every extra point of inflation.

Add it up: an extra point of inflation over the last ten years would have cost financial businesses $1.2 trillion dollars.

It’s enough to get a banker’s attention.

And that’s before you even consider the Fed powers-that-be in their roles as equity shareholders, and the Fed’s dual mandate. By emphasizing low inflation over low unemployment — and stomping on growth whenever the bogieman wage inflation threatens to rear its head*** — the Fed maintains a pool of unemployed and weakly compensated employees that cripples labor’s bargain power and empowers the steady growth of corporate profits over labor earnings.

It kinda makes you think about Mankiw’s fourth principle of economics: “People respond to incentives.”

I’ve said it before: if it weren’t for inflation, the rich really would own everything, instead of almost everything.

* Some will caveat: this is only true of unexpected inflation, because contracts are written with expected inflation in mind. The proper response: since the future is impossibly uncertain, all changes in the inflation rate are unexpected.

** Meanwhile economists fetishize notions about menu costs and the like, which in their largest estimations are an order of magnitude smaller than the inexorable arithmetic effect described here.

*** It’s happening now.

Cross-posted at Angry Bear.

Comments

40 responses to “Why the Fed Hates Inflation: 1.2 Trillion Dollars of Why”

“Meanwhile economists fetishize notions about menu costs and the like, which in their largest estimations are an order of magnitude smaller than the inexorable arithmetic effect described here”

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0776052/quotes?item=qt0364477

I am not sure why you say:

“Financial businesses are net creditors to the tune of $9-$14 trillion dollars”

because according to the same S.6.a table you quote, the net worth of financial institutions is much less.

@Ramanan

I knew I should have said: “net creditors in fixed-income assets, that have fixed payments and payoffs (or none of either — i.e. currency).” But I thought it was obvious.

I also didn’t explain that because of their fixed-income nature, those assets are much more vulnerable to real devaluation via inflation than equities and such, whose values are much more tightly linked to specific underlying real assets (“baskets of real goods”), so their prices move with inflation. Wanted to keep the post short and that seemed (somewhat less) obvious as well.

I actually thought of posting that net worth time series for you and JKH — negative or zero 2003-2007, going wildly positive in 2008, and declining since.

What macroeconomic story would you tell from that time series? This really isn’t a challenge of any kind. It’s a curious question.

In fact as the table shows, financial corporations have large nonfinancial assets and in fact they are net debtors – their financial assets are lesser than liabilities. (liabilities are always financial).

@Asymptosis

I’ll say that such as thing that have fixed income payments and payouts has no “strongness” as a concept.

I treat equity securities in the right hand side like a debt liability from a macroeconomic viewpoint. Firms do have to payout dividends. And in this sense, they should be considered as assets as well and can’t be removed in a meaningful way.

The real asset position of the financial industry is almost immaterial relative to the market value of equity

just took a look at what might be the ‘worst’ case among the Canadian banks – Scotiabank – the most international of the Canadian banks, with a relatively large capital investment in retail branching systems throughout the world

real asset value $ 5 billion

market value of equity $ 80 billion

the rest of the equity can be viewed in book value terms as offset by financial assets on the balance sheet, accumulated over time through retained earnings

(book value is ballpark $ 40 billion)

“What macroeconomic story would you tell from that time series?”

its very interesting

the net worth contribution of the market value of equity increases when the equity value plummets – see 2008

the net worth contribution of pension liabilities plummets (the liability value goes up) when interest rates fall (causing actuarial values to increase) in later years

that second point is why insurance companies have so many problems in a low rate environment

So do you guys think higher inflation is “bad” for financial businesses? Or would they at least see it as such?

Have to ask: relative to what?

Relative to lower inflation, ceteris paribus?

Or, my implicit relative: to the bottom 40-80% of households, which are net debtors?

Relative to nonfinancial business?

It’s really curious because it involves huge transfers (or “shifts”) in relative (and absolute?) buying power, without a single dollar being transferred between accounts.

I’ve been trying to figure how to depict these relationships (and inflation’s impact) in ways that mere mortals like me might understand.

On financial corps’ net worth, here’s the long series:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sWn

Wow. A rube like me would say, “you mean to tell me that following many years of steady growth in net worth, the financial industry crashed and was wildly insolvent for a decade?”

Something really weird happened in 1994.

Legislative changes 1994?

The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994, which repealed restrictions on interstate banking, listed the Community Reinvestment Act ratings received by the out-of-state bank as a consideration when determining whether to allow interstate branches.[49][50]

According to Bernanke, a surge in bank merger and acquisition activities followed the passing of the act, and advocacy groups increasingly used the public comment process to protest bank applications on Community Reinvestment Act grounds. …many institutions established separate business units and subsidiary corporations…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community_Reinvestment_Act#Legislative_changes_1994

This is just CRA-related, but still…

Suddenly financial institutions became too complex to comprehend?? (Hence too complex to regulate?)

late 90’s stock market boom drives up market value of equity which depresses IMA net worth measure, other things equal

its the opposite of insolvency

inflation is a non-issue for financials to the degree that there is a near nominal match between financial assets and liabilities – see my example point on Scotiabank above

must understand that the IMA net worth measure is directionally inverse to the value that the stock market puts on equity – other things equal – so is directionally inverse to the stock market’s assessment of solvency as well

very big bond market move in 94 as well – rates up

which depresses the value of actuarial liabilities

which increases IMA net worth – other things equal

@JKH “must understand that the IMA net worth measure is directionally inverse to the value that the stock market puts on equity – other things equal – so is directionally inverse to the stock market’s assessment of solvency as well”

I’m thinking very hard about this, having trouble but will continue.

Is this statement also true re: net worth of households and nonfinancial firms? Stock market goes up, net worth goes down?

Is “net worth” of financial firms a meaningful measure, absent the underlying? (It is for households, isn’t it?) Can you think of a different term for it?

IMA net worth is a technical, somewhat counterintuitive term and calculation

Basically, you put a market value on as much as possible, treat equity as a liability, and then calculate what is otherwise a balance sheet mismatch

So ALL other things equal, stock market goes up and net worth goes down

The opposite is true for households – because households have no equity (i.e. issued stock) liability – so if the stock market goes up, their net worth goes up when they own stock

BTW, this IMA/SNA net worth measure discussion goes directly back to the discussion you and I and Ramanan first had here 2 years ago

At that time, I was only vaguely familiar with the SNA/GL/now IMA net worth calculation and couldn’t quite understand it as discussed – recall a bit of confusion on my part then

It became clearer to me after looking at G&L

G&L by the way admit its a somewhat artificial calculation, designed to make matrices add up in their stock/flow analysis

My advice for what its worth is be very careful in using it more generally

“late 90′s stock market boom drives up market value of equity which depresses IMA net worth measure, other things equal”

“very big bond market move in 94 as well – rates up”

It sure looks like the big sea change in 94 was in stock market volatility (hence financial industry IMA net worth volatility?). Wow:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sWy

What caused that?

And once again, very different from conventional use of the term net worth in the case of any type of corporation – that’s typically a non-market book value calculation of book equity as the difference between recorded assets and recorded liabilities

And as is my usual theme, all of this stuff is reconcilable

But boy you’re really treading on particularly difficult territory when getting into IMA net worth calculations like this

Requires considerable dexterity – in particular in distinguishing between that net worth meaning and the more conventional and far more popular and still correct use of the term as the book value of equity

It’s very unfortunate that SNA/IMA has duplicated the terminology in this way – very unfortunate

My advice again is always when using this version to preface it as in IMA net worth or SNA net worth

@Asymptosis

MAJOR cyclical move in bonds in 94

(I was managing an interest rate portfolio at the time)

Fed moved on fed funds from 3 to 6 per cent fairly quickly and bonds moved up in concert/anticipation, which would be reflected in stock market vol

Oops revised graph, showing both as YOY % change.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sWA

Nothing particularly unusual seems to have happened in 94.

Why did fin corp net worth go from slow steady growth to craziness?

@Asymptosis

actuarial liabilities in 94

stock market boom later on

“you’re really treading on particularly difficult territory when getting into IMA net worth calculations like this”

I’m gettin’ that… Yes of course I understand it’s reconcileable. I’m after understandable.

“It’s very unfortunate that SNA/IMA has duplicated the terminology in this way – very unfortunate”

Yeah. Again, can you think of a better/different term or description for the IMA “net worth” measure?

And: my understanding from BEA writeups is that IMA is more SNA-compliant than the NIPAs. ??

(How many economists do you think can even begin to grasp this stuff? They should start with a required course in the philosophy of accounting.)

But look at 83 and 85. Same moves (rates down equities up), but without the wacky net worth effect.

Ah…maybe I should do real rates instead.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sWE

Still hard to see any obvious explanation there, given the violent change in IMA net worth volatility in 94.

Ooops fixed again (cpi yoy % change).

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=sWF

We do indeed see a historical anomaly in 94.

“Yeah. Again, can you think of a better/different term or description for the IMA “net worth†measure?”

Haven’t thought about that.

Godley/Lavoie say its not intuitive – very artificial.

But there’s one way it’s intuitive to me.

When SNA net worth is low, it means the market value of the stock is high, other things equal.

When SNA net worth is high, it means the market value of the stock is low, other things equal.

So when SNA net worth is high, it means intuitively that the stock is “cheap”, other things equal.

I.e. its attractively priced from an “investor’s” perspective

Thinking about it from a corporate stock buyback perspective, the managers may want to buy back stock (ideally) because the stock is cheap – i.e. there is a high net worth that the stock market isn’t recognizing directly – so the managers buy back the stock because they think the company’s IMA net worth is high – a direct reflection of a stock price that is “too low”

Doesn’t help with terminology, but that’s my personal intuition about it

“When SNA net worth is low, it means the market value of the stock is high, other things equal.”

You mean SNA fin corp net worth, right?

“Basically, you put a market value on as much as possible, treat equity as a liability, and then calculate what is otherwise a balance sheet mismatch”

And:

“Thinking about it from a corporate stock buyback perspective, the managers may want to buy back stock (ideally) because the stock is cheap – i.e. there is a high net worth that the stock market isn’t recognizing directly – so the managers buy back the stock because they think the company’s IMA net worth is high – a direct reflection of a stock price that is “too low—

Aha.

Thanks much for this. Starting to grok it.

“my understanding from BEA writeups is that IMA is more SNA-compliant than the NIPAs.”

really I think because it is an integrated set of accounts; remember NIPA is only one component of the integration – you need flow of funds/balance sheets to bring it all together

Accounting in large part is about a trip between a balance sheet at one point in time to a second point in time – NIPA gives you the trip that ends up showing you the change in the equity position (although remembering that whatever is consumed per NIPA during the period doesn’t end up on a balance sheet) – and NIPA doesn’t give you the additional flow of funds beyond that – e.g. NIPA won’t show you a “loans create deposits” change in a balance sheet – although it may indicate a consumption or investment flow that has been associated with that, it won’t give you that balance sheet change

But back to to the heart of the post:

Relative to each other,

Fin corps are long loans. Creditors.

Bottom 40-80% of households are short. Debtors.

Inflation transfers real buying power from A to B. ??

“You mean SNA fin corp net worth, right?”

Any entity (including financials) that issues equity to another party, or where there is a balance sheet equity position that is held as an asset by another entity

It’s the equity value liability treatment that mucks up the comparison with corporate accounting net worth

And that’s why it doesn’t affect households on the right hand side of the balance sheet – they don’t issue equity to another party

@Asymptosis

inflation affects the real value of all financial assets

which means everything except real assets on the asset side

which are minor

net lending positions in flow of funds/SFB include all that financial stuff

@JKH

affects nominal value of real assets as well of course

@Asymptosis

BTW – that buyback interpretation is my own – haven’t seen that anywhere else – e.g. its not in Godley and Lavoie – but that’s how I’ve wrapped my head around the idea

Maybe another way of saying it overly simplified – if you have a “cheap” stock, then ALL other things equal you may have a positive net worth – a net worth that is not currently being recognized in the value that the market is putting on the stock. As soon as it does, that net worth will disappear.

Regarding terminology – don’t know how to phrase it best, but the BASIC idea of IMA/ SNA net worth is that of a balance sheet mismatch – a market value of equity that is somehow out of balance with the way IMA/SNA wants to value assets and liabilities otherwise (including valuing equity as the market value of equity considered as a liability – a subtraction of value in other words). So the net mismatch can be reduced to a sort of mismatch in the market’s equity valuation, based on all those assumptions. Not sure what to call it otherwise, but I’ll think of something at some point.

I don’t rush language changes.

🙂

>which means everything except real assets on the asset side ”

Aside: But of course households’ primary real asset — their ability to work — isn’t even on the books.

Net debtor households benefit from inflation, right?

At least if we assume:

1. Fixed interest rate on their loans, and

2. Wages rise with inflation.

Ceteris paribus, they must benefit at some other entity’s expense. Like…the entity that they owe money to. Overwhelmingly, a financial business.

“a market value of equity that is somehow out of balance with the way IMA/SNA wants to value assets and liabilities otherwise”

That’s great. Really helpful. As always can’t tell you how much I appreciate your taking this kind of time.

@Asymptosis

OK!

Godley and Lavoie relate it to Tobin’s Q if I remember correctly, and Q is used as valuation metric, so I think you are on the right track for sure.

Someone needs to write Post Keynesian Economics for CFAs.@JKH

This is an interesting discussion, but to see why there is an anti inflation bias you just need very basic Marx.

Economic exchange in Capitalism is a M – C – M relationship. Money is invested to produce commodities which are sold for more money. This means that capitalists always have the expectation of a positive nominal profit. Even highly leveraged companies do not expect to go into financial distress. Therefore inflation always chips away at the real value of capitalist profits and will be hated.

If there is a “creditor class” is a harder question. It is right that American households moving to a net creditor position over the past 30 years is a rather unique and strange phenomenon?

Unrelated, but I am stealing this line, “Some will caveat: this is only true of unexpected inflation, because contracts are written with expected inflation in mind. The proper response: since the future is impossibly uncertain, all changes in the inflation rate are unexpected.”

@A H

AH,

Re Tobin’s Q, that occurred to me, although I didn’t recall seeing it in the book.

IMA wet worth = NW

Market value of equity = MVE

Tobin’s Q = MVE/replacement value = TQ

Then, I think:

TQ = MVE / (MVE + NW)

NW = MVE (1 – TQ)/ TQ

If the CFA program took a position on the preferred style for its economics component, then I think post Keynesian economics would be a PERFECT fit – with Godley and Lavoie the perfect text

The CFA program already takes a very intelligent approach to multi-disciplinary integration of economics, accounting, security analysis, portfolio management, etc. PKE would mesh extraordinarily well with that. Ironic that the CFA is ahead of economics itself in proceeding with that integration.

I wonder how many CFA types are familiar with PKE?

@JKH:

Been pondering this, as you can imagine.

>MVE/replacement value = TQ

>TQ = MVE / (MVE + NW)

So Replacement Value = MVE + NW

Strange, because most people would think off the cuff that MVE should equal net worth, right? Which should equal replacement value?

Can you give me a couple of more of those identities that include book value? I’m thinking book value is what you referred to as how the IMAs “want” to value the enterprise? That’s how I interpreted it.

[…] Why the Fed Hates Inflation: 1.2 Trillion Dollars of Why (Probably) Refusing to Quit Bill Black Slams New York Times for Wink and Nod Endorsement of Criminal Conduct My High School No Longer Holds Dances Because Students Would Rather Stay Home And Text Each Other Far from the Wolf of Wall Street: how did young people become so risk averse? Today’s bankers have replaced the excesses of the 1980s with Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations (related thoughts here) The responsibility of adjunct intellectuals The “Paid-What-You’re-Worth†Myth More on Ryan and Murray Virginia KKK Fliers: We’re Not The Enemy Of ‘The Colored And Mongrel Races’ The Real Debate Isn’t About “Life†But About What We Expect Of Women Buffett gets the better of everyone, version 4,762 Tea Partier: You’ll Go To Hell if You Vote for Common Core Ukraine: the Enemy of Your Enemy is Not Always Your Friend No One Does Charter School Stupid Like the Star-Ledger […]

[…] 1 pixel moon Guide to Convincing Parents to Vaccinate their Children Boosting the signal: THE SMALL TOOLS MANIFESTO FOR BIOINFORMATICS Zero senators per state Why the Fed hates inflation […]