I’m reminded of the joke about two ladies meeting at the races at Ascot.

“Oh dahling,” says the first, “what a wonderful hat. Where did you get it?”

The second, looking down her nose condescendingly and slightly embarrassed, sneers, “Dear, we have our hats.”

Do American employers have all the workers they need or want given the current state of the economy?

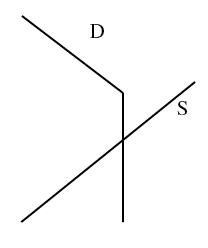

Do the supply and demand curves for labor (or at least lower-wage labor) look like this?

Now matter how much labor costs go down (widespread wage increases certainly aren’t in the cards), employers won’t increase the number of workers demanded; they don’t need them. (And you know: workers have all these pesky expectations and demands).

Recent trends suggest that for employers, investment in equipment and software is a preferable substitute for hiring. And substitution, of course, is the sine qua non of demand curves.

If this is the case, the only way to increase employment is to shift the demand curve to the right — making employers want more workers.

Which would undoubtedly have something to do with increasing demand for employers’ products and services. It’s hard to see how any shifts in the supply curve (i.e. workers caving and letting go of their sticky wage demands — the supply curve shifting right) could affect quantity in the scenario pictured above.

Comments

7 responses to “Is the Elasticity of Labor Demand at Zero?”

There’s an exact copy of your labour demand curve in Barro and Gordon 1971, and (if my memory is right) Patinkin 1965 appendix. And it’s kinked for exactly the reason you describe.

Quantity of labour demanded is whichever is less: the quantity at which the value marginal product of labour equals the wage (that’s the downward-sloping bit); the quantity needed to produce the goods the firms can sell (that’s the vertical bit). This all comes from Clower’s distinction between “notional” and “quantity-constrained” demand curves.

Thanks, Nick! I spent a bit googling before I posted, on the assumption that I wasn’t the first to think of this. Didn’t find anything (some about kinked curves, but not this exactly), thanks for the leads. I’ll follow them up.

Very clear three-paragraph explanation here, beginning “In order to ensure…”

http://books.google.com/books?id=sgBKtDRmzmQC&lpg=PA101&ots=SAFTIxwMZW&dq=Clower%E2%80%99s%20%E2%80%9Cnotional%E2%80%9D%20%E2%80%9Cquantity-constrained%E2%80%9D%20demand%20curves&pg=PA101#v=onepage&q&f=false

In the classical (read: freshwater) model, “all agents face infinitely elastic supply and demand schedules.”

And from Barro (who has a tendency to forget or ignore anything salty in his own findings when he’s pronouncing on policy) and Gordon, 1971:

“The essential implication of equation (1) is that the effective demand for labor can vary even with the real wage fixed. Given voluntary exchange, employment cannot exceed the effective demand for labor. The quantity of employment thus is not uniquely associated with the real wage.”

Asymptosis: I’m not surprised you didn’t find anything by Googling. Almost everyone has forgotten this stuff (if they ever learned it in the first place). It flowered briefly in the late 1970’s, then was swept away by the New Classical revolution. It’s important.

Google Malinvaud’s “Theory of Unemployment reconsidered”, disequilibrium macroeconomics, Clower, Leijonhufvud.

Search on “notional” on WCI to find my posts related to this approach.

Thanks again. I turned up your post pretty quickly, am studying it.

Sort of an aside: The notional vs effective thing has me wondering if there’s such a thing as “notional supply.” Example: the current quantity of funds “available” for business financing seems to be effectively infinite — zero scarcity, with actual (“effective”?) supply constrained by risk, not price: Much of that available pool is earning a negative risk-adjusted real “price,” so any real investment with a higher risk-adjusted real return should be sucking those funds in. What does that supply curve look like? Would it be useful to change the X axis to “risk-adjusted price”? Just pondering here, still.

I’m quite taken with the thinking in general, because I’m not at all taken with equilibrium as a useful concept in understanding economies.

Is the economy as complex as the weather system? To a first approximation, I’d say yes. Now imagine climatologists were using economics-style equilibrium analysis to study climate. Do you think they’d get anywhere? Is a sunny day (in Topeka) “in equilibrium”? A rainy day? How about 100 miles away? Does “equilibrium” even mean anything (useful) in those contexts?

I’m suggesting that with N markets all interacting, economies are never in equilibrium. Not so radical — most economists would casually agree, I think. But they still use it as a (indispensable) simplifying assumption in their thought experiments and models.

But I’d go farther: there is no such thing as economic “equilibrium” — at least in macro. The concept makes no sense. So it’s a fool’s errand to use it — even require it — in macroeconomic analysis. Except as a teaching device that’s stated in advance to be not only simplifying, but misrepresentative — one of Hicks’ “classroom gadgets.”

Keen points out this problem with “static” analysis in far more rigorous economics-speak than I can muster, and has actually built a (still rough) Godley-esque dynamic model that you can download and run. Just got a grant from INET to build it out. (Which leads me to wonder when those Santa Fe Institute guys are finally going to deliver something we can look at [they also got a grant from INET].)

I corresponded a while back with a young econ PhD candidate who was fascinated by dynamic, agent-simulation modeling. He said there was no way he could get a thesis approved on the subject — all the institutional powers were stacked against it. “Just grab a data set and throw some regressions at it, explain the results using (optionally, a slight variation on) currently fashionable theory. Collect degree.”

Given all that, I’m going to be diving into the Clowers, Leijonhufvuds, and Malinvauds of this world — cause somebody’s gotta theorize realistic algorithms to drive those dynamic models, and it seems like these guys may have started down that path. Thanks again.

Update: added “with N markets all interacting,”

Yep. The distinction between notional vs effective (constrained) demand applies equally well to supply.

Example: I supply zero labour (notional) as a mechanic. But if I were unable to sell my labour as an economist, I would supply 10 hours labour (effective) as a mechanic.

It’s not so easy to escape equilibrium theorising, if everything depends on everything else. Disequilibrium macroeconomists found they had to replace equilibrium in prices with an equilibrium in quantities. Not a market-clearing equilibrium, but a sort of equilibrium nevertheless.