Let’s adopt the unpresuming assumptions that:

1. A prosperous, modern economy needs a certain amount of government (taxing, spending) to become and remain prosperous. And that government has to be paid for via taxes and other government revenues. Simple enough.

2. Either too much or too little government in a country results in a poor economy, forcing the country to alter its taxing and spending policies.

So you won’t see any countries outside the workable range, because they’ll be forced back into it.

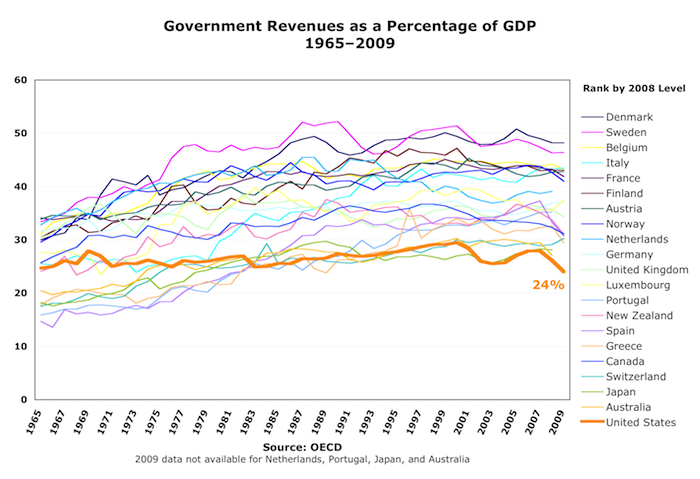

Now look at this:

Update: this is local, state, and federal taxes combined.

The first thing to notice: U.S. government revenues (local/state/federal combined) have been flat (with some short- and long-term wiggles) for 45 years. The notion of rampant increases is a myth.

Next: Note that the higher-taxing countries, in aggregate, have been seen long-term growth that’s basically equivalent to ours.

Let’s look at the other countries that are down there near us.

• Australia. They’ve been doing pretty well, but if Steve Keen is right (his arguments are darned compelling), they’ve been living on credit — especially housing credit (sound familiar?) — and they’re riding for a fall.

• Japan. ‘nuf said.

• Switzerland. It’s really amazing what a whole lot of international banks will do for the economy of a small country…

• Canada. As you can see, their average taxation rate has been way above ours for decades. Their rank here is an anomaly.

• Greece. Ahem.

• Spain. Ahem some more.

• New Zealand. I know bubkis about New Zealand’s economy.

• Portugal. Ahem ahem.

I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that since 1980 we’ve been teetering at the bottom edge of the range where a prosperous, modern economy can thrive. Eventually, we fell off the cliff.

Comments

21 responses to “More American Exceptionalism: Government Revenues”

Excellent, excellent graph.

And Keen is right.

Very interesting site. One key point of differentiation that many people fail to address is the relationship between services provided and tax burden – specifically, how much of the 16% of U.S. GDP is funded from the private sector rather than tax revenues? Adjust for that and I don’t think U.S. tax rates are quite so much of an outlier.

But I find your eye for relationships and interests thought provoking.

I would welcome your insights and reactions to a perspective I’ve been developing – a responset to the unintended consequences of our tax treatment of investment income. I urge you (or any of your readers) to take a look at http://www.2pctsolution.com/?p=578 which asks the questions “Could higher taxes stimulate more productive investments and growth?” Reactions, rebuttals and discussion would be highly valued.

@Douglas Hopkins “how much of the 16% of U.S. GDP is funded from the private sector”

I’m not sure what you mean here. Can you explain? What’s the 16%, and what do you mean by “funded from the private sector”?

Reading your posts, one key thing I find is what I think is a serious misunderstanding, one you share with almost everyone else: that taxing the proceeds from financial assets reduces the quantity of financial assets.

Because: the “tax it and you’ll get less of it” law is based on the principle of substitution. If the price of something goes up, you’ll buy something else instead. Putting aside the fact that you don’t “buy” financial investments (you’re actually lending): There is no substitute for financial assets (except real assets, which have the unfortunate characteristic that they decay over time, which financial assets don’t; at the end of the period you’ve still got the principal *plus* any returns on the principal).

If you sell your house for a million dollars — somebody hands you a suitcase of cash — what are you going to do with it? You can buy another house (or other real asset), or you can “invest” in some financial asset — lend it to others (yes, even stocks/equities are loans, just with different payment terms than a bond or other loan).

This illustrates a key insight from Randall Wray (*read* that man): the only way to store money is to lend it.

So taxing financial “investments” only reduces their quantity to the extent that it increases real investment.

[Wordpress for some reason posted this as being from “jkljkl.” I’ve fixed it.]

[…] More American Exceptionalism Asymptosis on why cutting back to the bone may not be such a great idea for the US economy. […]

While I agree entirely with the statement that “This illustrates a key insight from Randall Wray (*read* that man): the only way to store money is to lend it.”, I would humbly suggest that you do not attribute this insight (only) to Randy Wray, but also to our dear friend Marx. It was he who first showed/argued that money is a flow or process, which starts to break down and lose its value when it stops moving. Consequently, saving is at bottom ‘parasitical’ on the existence of those flows, and is only possible when a large enough percentage of the total amount of money keeps being (re)circulated.

The chart is good, but would be better if it took health care costs into account.

In ALL the other countries, the government carries a lot more of the health care burden than in the US.

Mind you, this is offset somewhat by the fact that the US seems to spend vastly more of it’s GNP on health care than any other country.

[…] Going to Cut Back The Bone and They’re Going to Keep The Fat George Washington’s Blog.More American Exceptionalism Asymptosis on why cutting back to the bone may not be such a great idea for the US […]

@Foppe Marx was fumbling toward an understanding of money, but I don’t think his view is terribly coherent. I think of him rather like Freud: groundbreaking, but not terribly useful or insightful in the age of Pinker.

@Kevin Smith I went looking once for “out of pocket medical costs plus insurance premiums per capita” by country, spent maybe twenty or thirty minutes, couldn’t find it or assemble it. Certainly not an authoritative time series since ’65 by country that covered many countries. If you can find it I’d *love* to chart it.

I would have to disagree with you there. It may be that my understanding of Marx’s work is too shaped by David Harvey’s (exegetical and developmental) work, but I never got the feeling that vol.1 is incoherent or too inchoate. Yes, Marx does not discuss how debt/borrowing fits into the system (he meant to do so in vol.3, but never managed to really work it out before he died), so that his theory of capital is incomplete, but I would not call it incoherent. If you have some time to spare, Harvey gives a very cogent introduction to the dynamic here: http://davidharvey.org/2008/06/marxs-capital-class-03/

(It is helpful to be somewhat familiar with A.N. Whitehead’s work — specifically “the Concept of Nature” and/or his book Process and Reality — as reading Marx through a causalist lens rather than a processual one generally causes confusion or frustration.)

How are state and local taxes, which are significant in the US but not in at least some of the comparison countries, taken inot account?

Total government debt in Australia is less than 20% of GDP, that is for federal, state and local combined. I think only Denmark has lower public debt in the OECD. What Steve Keen is very concerned about is the level of private, particularly mortgage debt here.

Mortgage debt in Australia has gone up from 17% of GDP in 1990 to 90% in 2010.

Households are starting to de-lever in a major way. Household savings rate has gone from minus 2% in 2000 to about 11% this year. So the retail sector, particularly high end discretionary, has taken a big hit.

There is a big factor to take into account when you compare government spending in Australia and New Zealand to the rest of the OECD. They began their welfare states in the 1890’s and chose a simple transfer system, that is, all welfare comes directly from general revenue and is income and asset tested. Very much “from each according to their income, to each according to their needs”. It is a pretty efficient system, very little churning or middle class welfare, so that’s a big chunk of GDP that never makes it into government revenue.

@Huskercr This is local, state, and federal taxes combined. Thanks for asking, I’ve added an update in the post.

@hanrahan Thanks for highlighting that: yes, Keen’s concern is about private, especially residential debt. Thanks also for the additional insights into Australia’s system.

@Foppe Thanks for the pointers. I’ll admit that I’m not going to follow them, though. The attempts at rationalizing Marx (and Freud) that I’ve read have been profoundly unsatisfying. I tend to find much more interest, for instance, in Joan Robinson’s “Open letter from a Keynesian to a Marxist.â€*

“When I am reading a passage in Capital I first have to make out which meaning of c Marx has in mind at that point, whether it is the total stock of embodied labour (he does not often help by mentioning which it is – it has to be worked out from the context) and then I am off riding my bicycle, feeling perfectly at home.

“A Marxist is quite different. He knows that what Marx says is bound to be right in either case, so why waste his own mental powers on working out whether c is a stock or a flow?

“Then I come to a place where Marx says that he means the flow, although it is pretty clear from the context that he ought to mean the stock.”

These are exactly the kind of problems I find when I read Marx. And (from what I’ve read that attempts it), I find them to be unrationalizable. So while I find some good thoughts and occassional Aha!s therein, it’s all too conceptually broken to help me clarify what I think.

Just to be clear: Marx is far from alone in failing to distinguish clearly and consistently between flows and stocks in his writings. Even top economics writers today are frequently inconsistent (and thus incoherent) in this regard. This is related to economists’ basic failure to understand what money is, hence what credit, debt, and wealth are.

Even the MMTers are troublesome here: they talk about sectoral “balances,” but what they’re discussing is flow balances, not stock balances. I’m thinking they’re generally quite consistent in what they intend by this locution, so they’re coherent and understandable as long as you’re conceptually clear on what they’re saying, but the use of the term “balances” in a flow context just contributes to the widespread confusion and confution.

* I *really* hate linking to anyone at the Koch-brothers-funded Mercatus Center or GMU in general ($30 million over recent years…), but, HT Tyler Cowen.

That’s too bad, because if there’s one thing Harvey’s not it’s that he isn’t a dogmatist. (see the lecture I linked to for an impression.) So while I am in total agreement with you/robinson when you note that such academics/scientists of any ideological persuasion aren’t worth the moniker, it seems to me that you’d be wrong in writing (Marx through the lens offered by) Harvey off as just another regurgitator.

—-

Having said that, I won’t dispute that getting Marxian “dialectical” (process) thinking is hard (though I would suggest that Hegelian dialectics are quite different, and that Marxists who refer to Hegel too much are misunderstanding him as well — they’d be much better off turning to Leibniz), and that people might simply find that it isn’t worth their time.

I myself am (I suspect luckily) coming at Marx after first having read quite a bit of Bruno Latour’s, Whitehead’s and Gabriel Tarde’s work, and this has made me look at the field of economics in a way that most economists would probably not appreciate (that is, I view economics as simply one social science among others, albeit one that often uses its quantitative approach to describing stuff in the world as an excuse for not taking the parts they’re having trouble capturing very seriously — see especially Friedman’s apparently fairly widely shared intuition that reductionist analysis and modeling are things to be praised rather than decried). Having said that, I am under no illusion that I can speak authoritatively on the topic of Marx’s capital.

whoops@grammar

Thanks for the thoughts, Foppe. I may take a meander into those areas. I love this:

“uses its quantitative approach to describing stuff in the world as an excuse for not taking the parts they’re having trouble capturing very seriously”

Things like, for instance, utility, non-remunerated work, and the value of government-provided (and unpaid-for) goods and services?

Yeah, stuff like that; public transport is an especially nice example (see http://one-salient-oversight.blogspot.com/2011/07/treating-rail-transport-as-commons.html ) where you often read how car manufacturers or toll road operators are against the development of new rail because it is “unfair competition through government intervention,” while at the same time they studiously ignore the fact that all kinds of costs associated with driving are subsidized to a huge degree by the government, which maintains the roads, subsidizes gas prices, and at times even subsidizes car sales, and without whose contributions those companies would simply go out of business. Though I guess the issue there isn’t so much that these things are impossible to compare the value of, but just that it’s very easy to do dishonest comparisons for political purposes.

Anyway, other stuff that economists like to forget about are, to name just 2 things: the “value” of having and rearing children (though this has already been monetized to a great degree — see the explosion of day care and pre-school facilities over the past few decades). Or the argument that society shouldn’t ‘subsidize’ education (esp. ‘luxuries’ like history, anthropology or philosophy), so often defended by taking the fact that there is no direct connection between having a population with a decently well-rounded educational background and GDP growth as proof of the fact that these things are worthless.

On the other hand, the tendency towards kicking people out of the hospital as soon as possible and letting family members care for them, so that the insurers have to pay less money to the hospitals doesn’t quite fit this trend. (Though it does in a different way — I’m sure you know what I mean.)

Anyway, the peculiarity of Tarde’s work is that he basically suggests that we should make all of the social sciences quantitative (in that they should be concerned with producing lots of different value hierarchies, comparing things in lots of different ways), but without trying to reduce those other measurement systems to the economic value measurement/expression system (money), so that money would no longer be the only quantitative and precise way of expressing social differences. (It’s a bit hard to explain in two sentences, sorry.)

I’m not quite convinced that this would work, as money is obviously much more dominant than other value meters, but at the same time, respect, education, etc., used to be much more influential in earlier times than they are now, so that it isn’t inconceivable to think that it is possible to make money-value comparisons less dominant as a way of expressing societal value.

A good introduction to this argument can be found in Latour & Lepinay’s recent work (fairly short; about 100 pages) called The Science of Passionate Interests: An Introduction to Gabriel Tarde’s Economic Anthropology. Latour’s writing style is a bit iconoclastic, but the argument they present there is intriguing, if nothing else.

Having to express everything in purely economic/monetary terms really makes for saddening reading.. Here’s another example, where the AARP is apparently so desperate for recognition that they’re trying to turn a terrible social issue into an “economic” one: http://www.npr.org/2011/07/18/138163839/aarp-finds-toll-on-family-caregivers-is-huge?ft=1&f=1003