I’ve been spending a lot of time lately pondering James Livingston’s insights on how modern, high-productivity, post-industrial economies work, as expressed in two of his posts which I link to and encapsulate here.

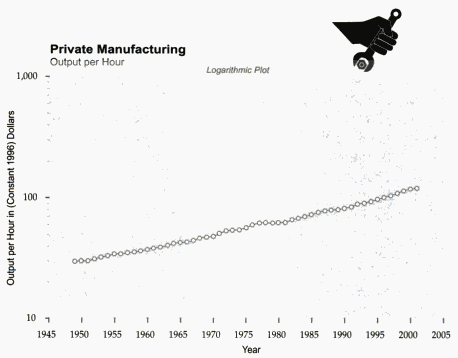

What finally closed the loop for me was re-reading Ray Kurzweil and others on past trends, and what the future holds: exponential growth in productivity.

Note the logarithmic scale.

I think I can best encapsulate my conclusions by asking a question: What would happen if labor productivity increased a thousandfold? So creating a certain amount of stuff/goods/prosperity currently requires a thousand workers; suddenly, it only requires one.

Imagine the world Kurzweil describes–in which one person using computer-driven nanotechnology can take the wood in your house and reconfigure the atoms into latticed nanomaterials sufficient to build several skyscrapers. It can convert a pile of dirt into a thousand Thanksgiving dinners. Who gets “paid” for that? (If this future seems fantastical, imagine living in 1508 or 1808 and looking forward to the way we live today. And remember: that efficiency is increasing far faster today, and the pace of that increase is itself increasing.)

Those 999 workers suddenly have no “legitimate” claim to any of that stuff, because they don’t do anything to “earn” it. Those kind of claims are inscribed in both law and practice, so those 999 workers don’t get any of that stuff/goods/prosperity/money. How could they? They’re superfluous.*

Put aside for a few paragraphs the ultimately inescapable issues of fairness, equity, and “just deserts.”** Can such an economy work?

No. Because those 999 people don’t have any money to buy the goods that the one person produces. And there’s no way that one person can purchase/consume all the goods produced. So they don’t get purchased. So they don’t get produced.

The economy–which is essentially a huge logrolling enterprise–stalls and stops.

This is a simplistic thought experiment. In particular, it assumes that the same amount of goods will be produced–ignoring the inevitable efforts of those 999 people to produce more goods, and get paid for them. (As productivity increases so the one guy can produce everything everyone “needs,” they will be increasingly unsuccessful in doing so because their labor becomes steadily less valuable.)

It’s simplistic, but it still represents–accurately and increasingly–the state of modern economies since the industrial revolution. The spectacular efficiencies of technology and corporate capitalism make labor (especially low-skilled labor) increasingly valueless. So in the real world a few people make a lot of money and a lot of people make less money. Absent some intentional intervention, it’s an inevitable result of rising labor productivity.

Left to its own devices, this system will inevitably grind (or crash) to a halt as more people fall off the log. That one person can’t keep it rolling while all the others drown nearby.

So why does the log keep rolling? Because of redistribution in modern, prosperous economies. It maintains the necessary level of “aggregate demand” as productivity increases.

Free markets don’t achieve that distribution or maintain that demand (as explained above, they work in the opposite direction), so government has to do it–for the good of all, including the one person standing there all alone on the stationary log.

It’s no coincidence that:

1. Every thriving, prosperous, modern country has significant redistribution systems–social support services, infrastructure spending, wage laws, labor protections, and yes, welfare. There are no exceptions. (The relative merits and demerits of those systems require far lengthier discussion.)

2. The two great economic crashes of the past century occurred when social support systems were at a historically low ebb, and inequality (in wealth and income) was at an apogee.

A certain amount of government–and redistribution–is not simply desirable in a high-productivity economy; it’s necessary for a modern economy to operate. The U.S.–taxing 28% of GDP compared to Europe’s 40%–has been the epicenter of both of the the aforementioned crashes. The only modern economies (of any size) that tax less than the U.S. are Mexico, Japan, and (barely) Korea.

At 28%, the U.S. appears to be teetering at the bottom edge of the range in which a modern economy can prosper and thrive.

Or…it’s already tipped off the edge–again.

* A semi-aside: who gets that one job? It looks decidedly like a matter of luck. Any number of the 999 could do the job just as well. Perhaps “merit” is the criterion, but merit is both widespread and difficult to gauge. Even if you use smarts and industry as the measures, let’s face it: some people are just lucky enough to be born smart and industrious; others aren’t. (And let’s not even get started on the lucky-sperm contest for being born wealthy.) Meanwhile, most of those 999 people have no hopes of landing the one job; remember that by definition, 50% of people have an IQ below 100.

** The “fairness” argument has justifiable legs. That one person does all the work, so that person “deserves” all the returns for that labor. Counter: those 999 people are out of work (or receiving low wages while working hard) through no fault of their own; given the huge prosperity that productivity and efficiency provide, don’t they “deserve”–just by merit of being alive–to live decent lives? See “luck” in the previous footnote.

Update: Wrestling with The Luddite Fallacy.

Comments

24 responses to “Why Prosperity Requires a Welfare State”

[…] explanation: because income is not widely distributed, aggregate demand cannot support productive industry, […]

I saw your comment and link over at Overcoming Bias – the Robin Hanson post on Ford, etc. I think you are on the right track here… the fact that the last 10-20 years in the U.S. the “economic growth” relied on ever increasing levels of debt points out that there is a strong need to have a mass consuming populous.

One problem with great inequality seems to be that the large piles of excess wealth continually search for income-earning investments, one cause, I think, of our bubble economy.

I don’t know if this article from Wired supports your thesis or contradicts it: http://www.wired.com/magazine/2010/01/ff_newrevolution/all/1

By the way, that s/b “just desserts”, not “deserts”. (albeit more amusing your way)

@BigSis

No.

http://www.google.com/search?hl=en&q=define%3Adeserts&sourceid=navclient-ff&rlz=1B7GGLL_enUS365US365&ie=UTF-8

Well I’ll be darned. Tells you never to assume anything. It got me to look into the etymology. It seems my mistake was not uncommon, and is probably due to the pronunciation.

America’s PRODUCTION system is outstanding, producing quality and quantities of food and goods at fair prices. We must encourage it.

Its our WAGE system that simply doesn’t work! Modify it by basing the dollar on the available consumer goods. Have retailers send an Economic Council the value of the goods on their shelves. Have employers send in each employees wage-rate and hours worked. Include a wage for homemakers, retirees, the military, students, etc, etc. Divide the value of goods so each gets a FAIR share. (FAIR means give a larger share to those who contribute best) Send each person a check.

TEAFS (available from amazon.com) explains why we must do this, and includes the formulas to divide fairly the value of goods. It says, “Let the Economic Council include a system to adjudge merit, making wages more fair. (Employers still get to set wages with their workers, as now.)

TEAFS will solve our nation’s economic problems.

George Richter

if there existed a machine that could make thanksgiving dinner out of dirt, why would those 999 workers need money?

I suppose you would’ve had the inventor of the textile mill shot for taking jobs away from tailors and housewives. Then too the fear was that the mill would lead to unemployment and lowered standard of living, but what we found instead is that more specialized jobs emerged in designing and manufacturing clothes. And now, believe it or not, there is a whole industry dedicated to getting clothes to consumers, and our standard of living has increased.

Similar to the many manufacturing innovations that sprouted up in the 18th and 19th century, these technological innovations will lead to unemployment, yes. But for every job that is lost, several more jobs will be created in the light of design and distribution. Oh and yes, our standard of living will increase when nanotech assembly makes food free.

Are you off your meds?

[…] looked at this in some depth — with much thinking help from Robin Hanson — here, here and […]

[…] even touched here on the idea that this redistribution may be economically efficient, even necessary, to maintain aggregate demand and support productive enterprises, keeping the log that is our […]

Can someone give me a reference to that remarkable log-linear plot?

Cheers,

Halstead

It’s from Ray Kurzweil’s book linked above:

http://books.google.com/books?id=88U6hdUi6D0C&pg=PA100&lpg=PA100&dq=kurzweil+labor+productivity&source=web&ots=v_e0nFvuLK&sig=H9Mky6AAXucBejCIKSESdNmDodc&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA101,M1

I agree completely and feel we really need to spread awareness of this growing problem in society. With the recent economic problems, there is a growing trend among conservatives to pull away from big government and welfare due to the thinking such “sharing” is a luxury we can’t afford in hard times. They blame the big government on the problems. This is a bad situation to face. How do you convince someone that more welfare spending is the solution, when they already believe the problem was caused by too many taxes, and too much government spending?

I would also stress that the largest problem here is the inequity, more so than the concept of the collapse of the economy. The growing productive created by growing technological development causes the devaluation of labor, and the increased valuation of capital. Those that have the money, and are best at investing it, are the ones that will end up controlling all the resources. Capital naturally concentrates and forms monopolies. The more wealth an individual or corporation accumulates, the more power they garner to distort the free markets, so as to protect and further grow their monopolies. Though in theory a democracy based on one vote per individual should pass and enforce laws that treat the entire population fairy, the practical truth is that money buys both votes, and legislators and eats away the very foundation of the democracy. The growing wealth inequity, creates a growing weakening of our democracy. If we wait too long to act, the people will no longer have the power to vote their democracy back. Big money will have taken our government away from us.

I strongly advocate a direct redistribution of wealth to replace many of this indirect social services provided by our governments. The big money should be taxed, and the revenue should be redistributed to the people as a purple wage. It should start out very small, but grow over time as technology advances and puts growing numbers of people out of work – or just reduces the market value of their labor to pitiful levels.

We are only a handful of decades away from the time where robots and AI technologies will replace everyone in the job market. When we get there, we will end up in a society where no one can work for a living, and wealth and power will be controlled only by who owns all the resources, and the machines, and the technologies. People won’t even be able to buy land to farm because the big money will have bought control of all of it. If we want to survive as a society of billions of humans, instead of as a society of 10,000 super wealthy, we will need to convert to a system where the resources, and technology, and production systems, are shared (at least to some extent). We need to tax the big money, and redistribute the cash to all the people (not just the needy, but to all of them).

@Curt Welch

Thanks Curt. Glad you liked it.

I think the reason we’re so disappointed with Obama is that he has not changed the conversation fundamentally, in this direction. He’s still bought into the precepts and tenets of Reaganomics.

If a person is unable, through no fault of his own, to make a claim to a decent share of the pie, does that mean he doesn’t “deserve” a share? I say no. When tens of millions of people are in that situation, and that number is increasing, I say ten million times, No.

During the interim between now and when automated machina and AIs deprecate the job markets, we will need to change how and why wealth is distributed. It is my dream that politicians of the future will aim for work destruction rather than job creation. It irks me to no end to think of how irrational we are that we have to ‘create jobs’ for people or else they will starve. When we ‘create jobs’, did we really need that work to be done? No. Look at the trucking industry. The main reason we stopped using rail for all our transportation is because trucking creates hundreds of thousands of job…

I am not comfortable with basing current actions on predictions about the ultimate end of technological innovation {when there is no need for human labor to provide for human needs}, however, I am obsessed with how we can transition towards such ends; with how we can most efficiently go with that flow. In order to deprecate the current system gracefully we will have to implement the redistributions gradually, as Curtis mentioned. Until we can demand “Earl Grey, Hot” and have nanobots build it for us, we’re going to need an economy and systems of work and business.

One theory I’ve had about this transition would be to change where money comes from. Rather than a government of taxation, borrowing and spending, in which a small group of politicians decide when to borrow more money into the system, we simply back all human labor with new money. Start out small, just a bonus for everyone that works, but eventually scale up the amounts to replace all wages with labor-backed money. The price of all commodities, especially those not based on physical resources, would plummet {as quickly as the new money supply is scaled}. In fact, raw physical resources would be the only monetary cost of most products; if we take paying for labor out of the equation, the price of all goods is just atoms and energy. Competition would recede in favor of collaboration; all businesses could run as open source projects, where experts of every field would rally around whatever project they feel has merit; the only limit to consumption would be the availability and sustainability of physical resources {as common sense would like}.

To offset hyperinflation, any money used to pay for physical resources should be destroyed instead of recirculated. Mathematically speaking, one could imagine humans under this system achieving homeostasis with the Earth {as opposed to our current sub-exponential hunger}. Prices are set based on how much Earth it takes to make the product, wages are set based on how much more than the basics of life we can provide for ourselves, and the value of our money will fall if everyone decides to work more.

It would be self-regulating and in tune with any finite limits on real physical resources.

Under such a system, one could imagine a welfare state in which everyone gets the basics they need to survive, and the comforts and cutting edge tools are there for anyone that wants to work to get them. Anyone that doesn’t have any “real work” to do providing goods and services can just be an artist, or even better yet, a good parent or friend who isn’t a stressed from working 60 hour weeks… All we need to tip the balance is enough automation that we can afford to take care of everyone’s necessities, plus a margin of physical wealth that will only grow as our techne evolves ;-}

…Oh, and we’d need politicians to implement it. But, that is a different sort of social problem that can easily be solved with e-democracy. =}

This problem seems so.painfully obvious that it is often ignored.there seems to be a disrurbing trend in some countries whereby the pooree people are being demonised and yes beyond a certain point wealth isnt extremely desirable.

Labor is the scarcest of the factors of production as long as there are still resources that remain unexploited and not all human wants are satisfied. Technological progress reduces want, it does not produce unemployment. This an economically illiterate position – if it were true, the Luddite destroyers of automatic looms would have been correct, but they were not. In fact, unemployment would, according to this theory, have been rising since Ugg invented the first hand ax in the stone age, which at the time delivered an unprecedented increase in productivity. The error of this position is that it regards the economy as static, but the economy is highly dynamic. As an example, who knew 40 years ago that there would one day be people writing blogs? That there would be ‘web masters’? What you fail to consider is that new industries will come into existence, creating jobs which we can not yet conceive of. Perhaps in a century there will be great demand for space ship engineers, who knows? However, one thing remains absolutely certain – unless the planet’s population grows so large that all the productive factors needed for food production are fully employed, there can NEVER be ‘technological unemployment’ due to an increase in productivity. This view fundamentally misconceives how the economy works.

@pater tenebrarum Pater, I’ve considered the Luddite Fallacy (Fallacy) at some length. Could start here and follow the links (also see Related Posts at the bottom of each post):

http://www.asymptosis.com/yes-machines-are-replacing-humans.html

Also be aware that (as you’ll see in the discussions above), I am far from alone in these considerations. Even the Koch-funded GMU crowd talks about this stuff a lot, and not in the simplistic and utopian terms you deploy here. Arnold King was poking at it just yesterday:

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2012/08/the_great_facto_3.html

My intuition — which I still haven’t worked out as cogently and coherently as I would like — is that the Luddite Fallacy Fallacy is rooted in a failure to consider marginal utility of consumption. Buying a second or third Lamborghini doesn’t deliver the same utility per dollar spent as putting your kids through college or getting your mom the heart bypass she needs.

[…] spent a lot of time considering (here, here, here, and here) the notions of technological unemployment and the Luddite Fallacy: the idea […]

[…] 21, 2012 by admin I’ve spent a lot of time considering (here, here, here, and here) the notions of technological unemployment and the Luddite Fallacy: the idea […]

I bought a book called “Death by Technology” out of curiosity. It changed my whole way of thinking about technology and why we’re having so much trouble with the economy. He laid it out brilliantly and it all boils down to one underlying problem in a nutshell. I think our inability to control the rapid advancement of our technology has caused us to run off a cliff. Today is nothing like the crash of 1929. It’s much worse in so many ways it’s scary. Peak oil, peak employment and economic collapse are all connected to technology.

[…] has long seemed to me that redistribution is, for some reason, necessary for the emergence, continuance, […]

Human beings will trade with this highly efficient robot and still make a living.

For example,there are robots which make a million cakes/hour as well as a million life saving drugs/hour. The latter is ofcourse more valuable and the economy would be better off if the robot could spend its time making the drugs instead of cake.Human beings would be hired to make the cakes in this case,freeing up the the robot to pursue drug making -benefitting everyone including the humans who now will earn a high compensation because of the opportunity cost it saves the robot(we are speaking of high value drugs here).

Like the US which has absolute advantage in making both electronics and clothes compared to Bangladesh,still benefits by trading with it in clothes.

No welfare state is necessary. Trade and exchange will do the redistribution. Ofcourse human beings will need to know how to make cakes!